Next Wednesday on PBS Nature…

Back in the 1990’s biologist and wildlife artist Joe Hutto spent two years in the Florida Flatwoods as mother to a flock of wild turkeys.

It began when a neighboring farmer dropped off a clutch of 16 orphaned wild turkey eggs and Joe decided to imprint them.

When the eggs hatched Joe made sure the first pair of eyes they saw were his own. The hatchlings immediately recognized him as their mother and thus began the strange and wonderful journey that became his 1998 book, Illumination in the Flatwoods.

My Life as a Turkey shows what happened, the joys of discovery and the sadness of death, as the peeps became poults and then adult birds. Day after day, week after week, Joe’s bond with his turkeys grew stronger. The more time he spent with them, the more he learned and the less detached he became. He was their parent, they were his family. He learned to live in the present as they did. He often felt more turkey than human.

My Life As A Turkey is beautiful, moving, sad and fascinating.

“Had I known what was in store—the difficult nature of the study and the time I was about to invest—I would have been hard pressed to justify such an intense involvement. But, fortunately, I naively allowed myself to blunder into a two-year commitment that was at once exhausting, often overwhelming, enlightening, and one of the most inspiring and satisfying experiences of my life.”

Don’t miss My Life As A Turkey next Wednesday, November 16 on PBS Nature. On WQED it’s at 8:00pm.

You will never look at a wild turkey the same way again.

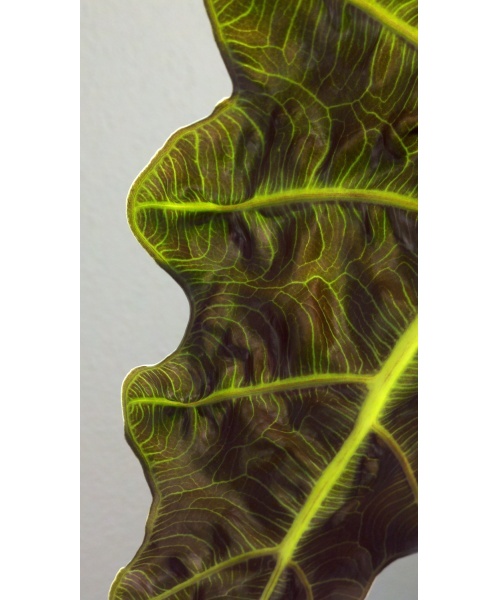

(photo from My Life As A Turkey)