7 September 2010. Updated June 2018:

This seabird is so rare that we thought it was extinct for more than 300 years.

The Bermuda petrel (Pterodroma cahow) nests in only one place on earth — the islands of Bermuda.

Locally it is called the cahow because of its eerie voice, a voice so odd that when the Spanish discovered Bermuda in 1505 they refused to settle there because they thought the islands were haunted by hundreds of thousands of devils that called “cahow” in the night.

In 1609 a British ship wrecked at Bermuda and in 1612 British settlers came to stay. Soon their crops failed and they ate the cahows — all of them. Within four years cahows were impossible to find and by 1620 they were presumed extinct.

Miraculously a remnant population survived, hidden from man because the birds spend their lives on the open sea, visit land only on dark nights during the nesting season, and nest deep in burrows on small inaccessible islands.

Storms both revealed and threatened the cahow’s existence. In 1935 a mystery bird was found dead below St. David’s lighthouse after a violent summer storm. Sent to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, it was identified as a cahow. In 1945 another mysterious dead bird was found on the beach and again it was a cahow.

These discoveries spurred young David B. Wingate to look for the bird. At age 15 he joined the official search to find it and in January 1951 was one of the three who first saw the bird that was missing for 330 years. It was almost too late. There were only 18 nesting pairs left.

David Wingate dedicated his life to bringing the birds back from extinction. Nearly 70 years later, the cahow is now the national bird of Bermuda and, thanks to his leadership, it is protected and more numerous. Even so there are only about 250 individuals in this species. It is still very rare.

Read more here about the Bermuda petrel. See videos from the Cahow nestcam hosted by Cornell Lab. Learn about the Great Start to 2018’s Nesting Season, 125 pairs!

(photo of a cahow from Wikipedia. Click on the photo to see the original)

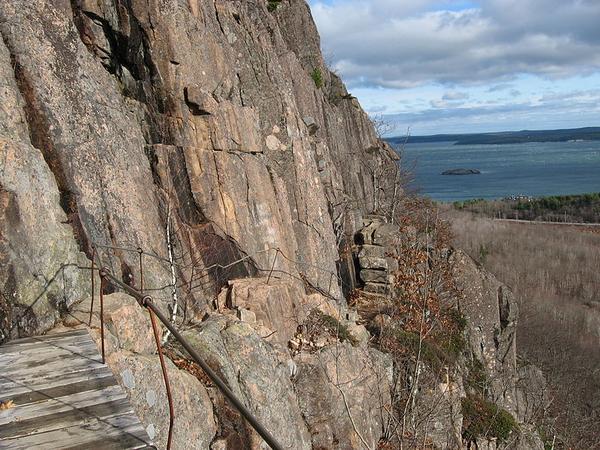

Not many shorebirds at South Lubec yesterday, which was disappointing for my shorebird study, but I went to Campobello Island (New Brunswick) and saw whales, seals and ocean birds very close to shore at East Quoddy Head Lighthouse. There were black-legged kittiwakes, razorbills, common murres, red-necked phalaropes just off shore.

Not many shorebirds at South Lubec yesterday, which was disappointing for my shorebird study, but I went to Campobello Island (New Brunswick) and saw whales, seals and ocean birds very close to shore at East Quoddy Head Lighthouse. There were black-legged kittiwakes, razorbills, common murres, red-necked phalaropes just off shore.