One of the most fascinating things about birds is that they can perch while asleep and not fall off the branch.

We know from experience that our hands can grasp while awake, but when we fall asleep our hands relax and we drop what we’re holding.

Why doesn’t this happen to birds? Why don’t they fall off the perch when they fall asleep?

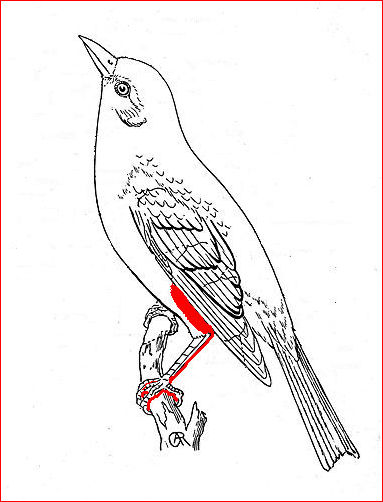

Songbirds’ feet work quite differently than our hands. Perching birds have a long tendon that starts at the calf muscle, extends around the back of the ankle and travels down the insides of each toe. When the bird squats the tendon is pulled tight and it, in turn, pulls the toes closed. When the bird stands tall, the tendon relaxes and the toes open.

In the illustration above I’ve drawn the calf muscle and tendon in red. The “ankle” is the sharp bend in the bird’s leg shown just under its wing. According to Frank B. Gill’s Ornithology, songbirds also have a special system of ridges and pads between the tendons that assist the natural locking mechanism.

So when a songbird relaxes, its feet grasp more tightly. Songbirds sleep without slipping.

(Image altered from Chester A. Reed, The Bird Book, 1915. In U.S. public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Click on the caption to see the original.)