Imagine listening to birds without the sounds of human machinery in the background. That’s what our world was like when Aldo Leopold was alive.

In 2012, ecologists Stan Temple and Christopher Bocast from the University of Wisconsin-Madison recreated a 1940 soundscape at Aldo Leopold’s shack in Salk County, Wisconsin. The project was amazing because they didn’t have a recording from Leopold’s time. Instead they built it from his field notes.

Every morning Aldo Leopold listened to the birds and wrote detailed notes of the songs he heard, where he heard them, and the light levels when the birds first sang. Using his notes, bird song recordings from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macauley Library, and newly recorded background sounds from Wisconsin, Temple and Bocast completed the soundscape.

The result is nothing like the place today. The habitat, birds, and insects have changed and now there’s the constant hum of an interstate less than a mile away.

To get “clean” background sounds Temple and Bocast searched for a quiet place in Wisconsin. It was very hard to find because, as Temple points out, “in the lower 48 states, there is no place more than 35 kilometers [21.7 miles] from the nearest road, making it nearly impossible to tune out the hum of human activity, even in places designated as wilderness.”

I’m familiar with the problem. I’m used to noise near my city home but I go to the woods to be quiet and listen to nature. In the last 15 years I’ve noticed an increase in human-generated sounds in the woods. It’s impossible to avoid the sound of cars, trucks, trains, motorcycles, airplanes, chain saws, all-terrain vehicles, boats and jet skis.

I don’t like it. Perhaps I’m not alone.

On Sunday I watched a flock of robins in the trees along the Bridle Trail in Schenley Park, directly above the Parkway East. I tried to locate the birds by sound but could not hear them over the roar of the interstate.

The birds probably couldn’t hear well either. It was more than annoying. It was stressful.

I wonder what they think of ubiquitous human noise.

Click on the photo above or on this news article at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Then scroll down and click on the Soundscape link to hear what Aldo Leopold heard.

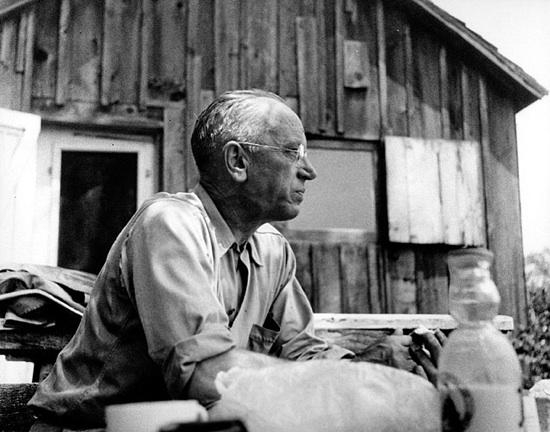

(photo of Aldo Leopold, courtesy UW Digital Archives. Click on the image to read the article and listen to the recreated soundscape.)