Throw Back Thursday (TBT):

What do pigeons have to do with the Internet?

Here’s a look back to 2009 when an Internet connection speed was challenged by a bird –> Faster Than The Internet.

(photo by Chuck Tague)

Throw Back Thursday (TBT):

What do pigeons have to do with the Internet?

Here’s a look back to 2009 when an Internet connection speed was challenged by a bird –> Faster Than The Internet.

(photo by Chuck Tague)

Soras (Porzana carolina) are the most abundant rail in North America but they’re so elusive that we rarely see them fly. When disturbed they prefer to walk deep into the marsh rather than go airborne. If you happen to flush one it looks weak and labored in the air.

Though they appear to be fly poorly, soras migrate long distances. They’re very cold sensitive so they have to leave before the weather turns. Birds of North America says they become lethargic as the temperature approaches freezing so “most soras winter in areas that have a minimum January temperature above –1°C (30°F).”

From their breeding grounds in Canada and the northern/western U.S. to their wintering grounds in the southern U.S. and Central and South America, soras may fly up to 4,000 miles. We don’t see them on migration because (presumably) they fly at night but they’re sometimes found resting on ships hundreds of miles offshore. We know they cross the open ocean. Some of them winter in Bermuda and the Caribbean.

This month soras are hanging out in wetlands en route on migration. If you’re lucky enough to see one, think of its journey — reluctant to fly, except to escape the cold.

(photo by Robert Greene Jr)

When we humans have time off, some birds go to work. In this video from Odolanów, Poland, hundreds of racing pigeons start on a race.

Racing pigeons are rock pigeons (Columba livia) specially bred and specially fed to be fast and athletic. Their owners know the birds must be fit and healthy to win. They take really good care of their birds.

On race day the pigeons are trucked to a central starting point and released to fly home. The trucks are specially designed to carry the birds and release them simultaneously. Race officials note the start time for each group and stagger the releases so the birds have enough space to circle up, get their bearings, and leave. As they circle, each pigeon figures out where home is — and then flies as fast as he can to get there.

How do they determine which bird wins? Race officials note the time the bird was released. The bird wears a band that’s electronically read when he arrives at the loft and notes his finish time. The racing organization calculates the distance from the release point to the loft. The fastest bird in miles/kilometers per hour is the winner. Ta dah!

For more information on pigeon racing, click here.

(video from YouTube)

On my August 23 outing in Schenley Park, we found something near Panther Hollow Lake (pond) that we’d never seen before: a pair of Asian lady beetles mating.

Asian lady beetles (Harmonia axyridis) are the non-native species released in Pennsylvania years ago to control aphids. They’re now so successful that they’re annoying, especially when they invade our houses in the fall.

As the pair embraced on a plant stalk, we noticed the male was smaller than the female and that she stood still while he was rocking. They were mating when we found them and they continued after we walked away. Who knew that bugs had so much stamina.

The female beetle may have laid a lot of eggs afterward but we won’t be overrun by her offspring. The bugs were on the dirt pile created by Public Works when they fixed the pond overflow last spring. After a long hiatus the pond project resumed on August 24. Now the dirt pile and plants are gone.

These two are “lady beetles” but only one of them is a lady.

(photos by Kate St. John)

p.s. Here we are before we went down to see the lady beetles.

September is the month for asters and goldenrods but these plants are so hard to identify that I usually say: “It’s an aster (or goldenrod) but I don’t know which one.”

Now there’s hope for the aster-onomically challenged. Pennsylvania Botany is offering a one-day seminar on identifying asters and goldenrods on September 22 at Nescopek State Park. Participants will use keys and floras and get plenty of hands-on practice.

Master asters at this seminar. It’s open to the public but is not free. See the links below for more information.

Aster and Goldenrod Identification Workshop

September 22, 2015 • 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Nescopeck State Park, Environmental Education Center

1137 Honey Hole Road • Drums, Pennsylvania 18222

Directions/information on Nescopek State Park.

(photo by Kate St. John)

Today is International Vulture Awareness Day, the day when we remember vultures under threat and thank them for saving us from disease.

Originally founded by Birds of Prey Programme in South Africa and the Hawk Conservancy Trust in England this annual event teaches the benefits of vultures and our actions that threaten them.

The most famous vulture crisis happened at the turn of this century when public health officials, conservationists, and birders became alarmed that 95% of the vultures in India, Pakistan and Nepal had died-off in only 15 years. It was the fastest bird decline in history and became painfully obvious when the landscape was swamped by decaying animal carcasses. Research revealed that the solution was rather simple: Ban diclofenac, a painkiller given to cattle that’s deadly to vultures. The drug was banned in 2006 but vulture populations are severely damaged — down 99.9% — perhaps irretrievably.

Vultures in Africa and Europe are declining as well and could face extinction within our lifetime. In Africa the threats are complex; click here to learn more.

If you think our vultures are secure, think again. The largest land bird in North America, the California condor (Gymnogyps californianus), is a vulture and is so critically endangered that they’ve been captive-bred since 1987. Every California condor you see today comes from that program.

And in South America Andean condors are near-threatened. You can see and learn about them at Pittsburgh’s National Aviary.

Thankfully our turkey and black vulture populations are stable, but we often don’t realize the good work they do for us. They usually eat carcasses before we smell them and save us from the diseases harbored in rotting meat. Did you know vultures can eat anthrax safely because their powerful stomachs protect them? Thank you, vultures!

So when you see a vulture today give him a nod and thank him for his efforts.

Happy International Vulture Awareness Day!

(turkey vulture photo by Chuck Tague)

Broad-winged hawks are on the move. By the middle of this month their numbers will peak at Pennsylvania hawk watches.

In summer broad-winged hawks are secretive but by late August the birds have finished breeding and are ready to start their journeys to Central and South America.

Unlike most raptors, broad-wings travel in flocks, rising together in thermal updrafts, gliding out toward their destination. At the bottom of the glide they find another thermal and rise again. From a distance they look like rising bubbles so the flock is called a “kettle.” The video above shows them gliding. Click here to read more about kettles.

Thermal updrafts are best over sun-heated land so the hawks avoid flying over lakes and oceans. As they move south, the flocks grow in size and become concentrated at the northern edges of the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico. By the time they reach South Texas there are hundreds of birds per kettle and half a million broad-wing hawks per day.

To really see the sky filled with birds, visit the hawk watches at Corpus Christi, Texas or Veracruz, Mexico’s River of Raptors in the last week of September and the first week of October.

The video below shows broad-wings over Corpus Christi. One kettle contains well over 1,000 birds!

(videos from YouTube. Click on the YouTube logo to see more information about the video)

Throw Back Thursday (TBT):

Birds aren’t the only ones migrating right now.

In the early 1990’s scientists discovered that some dragonflies migrate, too. Here’s the story in a September 2008 blog post: Bug Migration.

(photo by Chuck Tague)

2 September 2015

Here’s the leg of a ruby-throated hummingbird, so short that the toes make up nearly half its length.

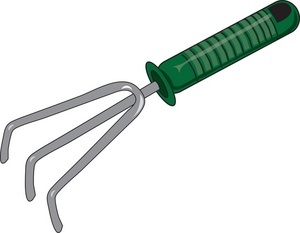

Look closely and you’ll see the foot resembles a garden claw.

.

This group of birds also has tiny feet shaped like garden claws.

.

Once you know their feet are similar, it’s not a big leap to realize that these birds are related.

Swifts (Apodidae) and hummingbirds (Trochilidae) are in the same the taxonomic order Apodiformes, a Greek word that means “A”=no, “pod”=foot.

“No feet.” 🙂

p.s. Click here to read more about the similarities between hummingbirds and swifts.

(hummingbird photo by Kate St. John, garden claw clip art from clipartbest.com, white-throated swifts illustration from the Crossley ID Guide for Eastern Birds, Creative Commons license, via Wikimedia Commons. Click on the images to see the originals)

With songbird migration underway, here’s something to think about when you see a blue-winged, golden-winged, Tennessee, orange-crowned, or Nashville warbler: Their beaks make a strong opening.

Back in July at Cunkelman’s Neighborhood Nest Watch banding, Bob Mulvihill’s mist nests captured an immature blue-winged warbler (Vermivora cyanoptera). With the bird in hand he put his fingers lightly on the bird’s beak and it immediately opened its beak and pushed Bob’s fingers away. What an unusual talent! These warblers have extremely strong gaping muscles.

Golden-winged warblers, closely related to blue-wings, are so well studied that this fact is mentioned in the literature about them. Bob has also found it to be true of the (formerly*) Vermivora warblers and oriole species he’s banded in eastern North America.

Why this unusual talent? Vermivora literally means “worm eater” — vermi:worm, vora:eat. The “worms” are small caterpillars (not earthworms) that hide among leaves, often wrapped in cocoons or in curled up leaves. The warblers open the rolled leaves against the caterpillars’ will.

When you see these talented birds watch them probing among the leaves. They’re making a strong opening.

(photo by Kate St. John)

———————————————–

And what’s all this about formerly(*)?

The genus Vermivora used to contain nine species including Tennessee, orange-crowned, Nashville, Virginia’s, Colima and Lucy’s warblers, but in 2010 the American Ornithological Union transferred all but Bachman’s (extinct), blue-winged and golden-winged to the genus Oreothlypis. After years of having nine Vermivoras, it’s hard to keep up with the changes.