Twenty-one years ago I attended my very first hawk watch on a spectacular golden eagle migration day — 26 October 1996 at the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch.

Nowadays when I want to see a lot of golden eagles I visit the Allegheny Front in early November because that’s when the eagles fly by. Is it my imagination or are the birds migrating later than they used to? A new study published last month in The Auk: Ornithological Advances confirms that raptors’ autumn migration has shifted later.

The study, conducted by Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, analyzed hawk count data for 16 raptor species from 1985 to 2012 at 7 hawk watch sites in eastern North America: Hawk Mountain Sanctuary (Kempton, PA), Hawk Ridge (Duluth, MN), Holiday Beach (Ontario, Canada), Lighthouse Point (New Haven, CT), Montreal West Island (Québec, Canada), Mount Peter (Warwick, NY), and Waggoner’s Gap (Landisburg, PA).

The 16 species included both long distance migrants traveling to South America such as broad-winged hawks, and short distance migrants that stay in North America such as sharp-shinned hawks and golden eagles. Each species adjusted its peak migration, but the delays were pronounced for short distance migrants.

To parse out the reason why raptors stay north longer, the study compared climate and air temperature data in the birds’ breeding areas to the timing of migration during the 28 year period.

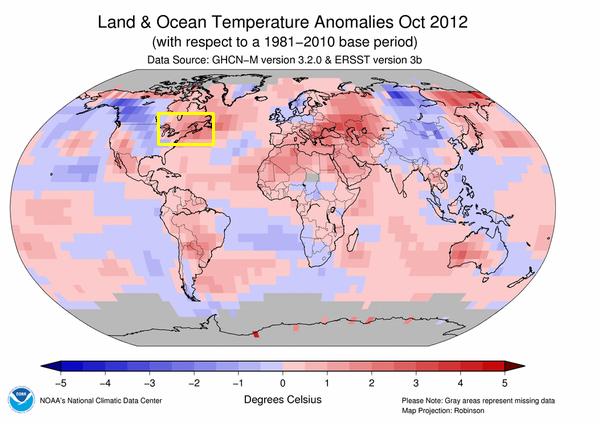

As you can see from this NOAA map from October 2012, the climate warmed in the breeding zone in eastern North America (marked with a yellow square). Click here to see the details on the study’s map.

Because the warming climate delays the first frost, plants and insects remain abundant later in the year. This abundance ripples all the way up the food chain to raptors who postpone their fall departure. The study found that the shift in migration matches the pace of warming climate.

Golden eagles demonstrate the trend. Between 1985 and 2012 they waited an additional 0.16 days/year before moving south. By 2012, the delay was 4.48 days. Extrapolating to 2017, golden eagles are leaving 5.12 days later now than they did in 1985.

Whats’ more than five days after October 26? November 1. So I’m going to the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch in November.

Click here to read about the study and download the full report.

p.s. Three species have delayed autumn migration even more than golden eagles: Sharp-shinned hawks added 0.2 days/year, northern goshawks added 0.21 days/year and black vultures added 0.40/year.

(photo by Steve Gosser)