27 May 2023

Imagine spending a day standing on dunes in cold wet weather and seeing a river of a quarter million warblers fly by. This amazing phenomenon was the perfect storm of location, migration and bad weather.

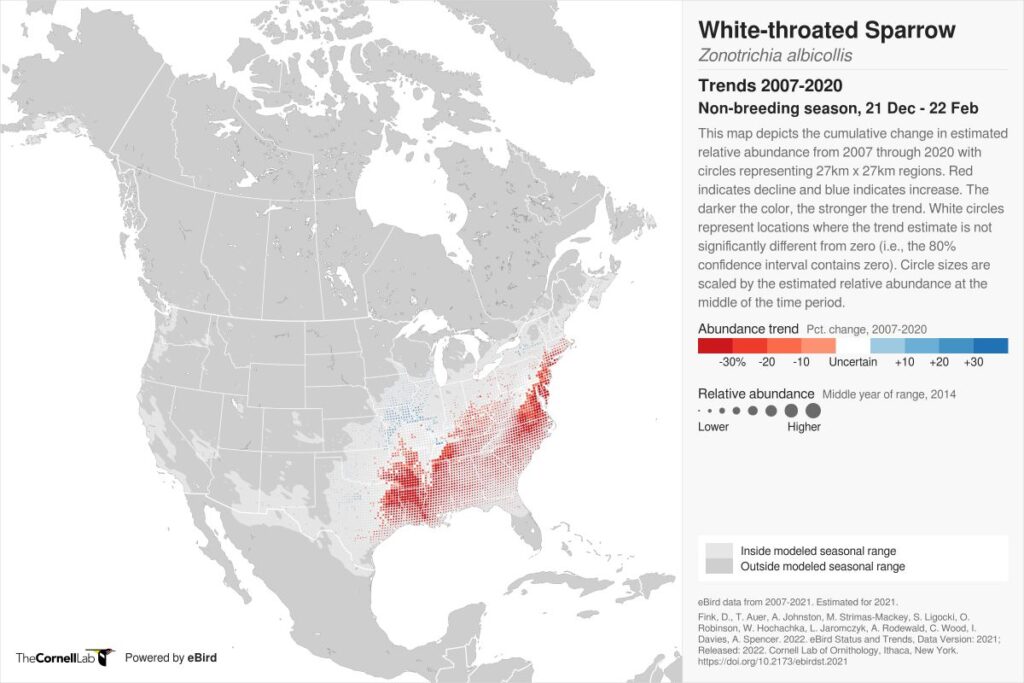

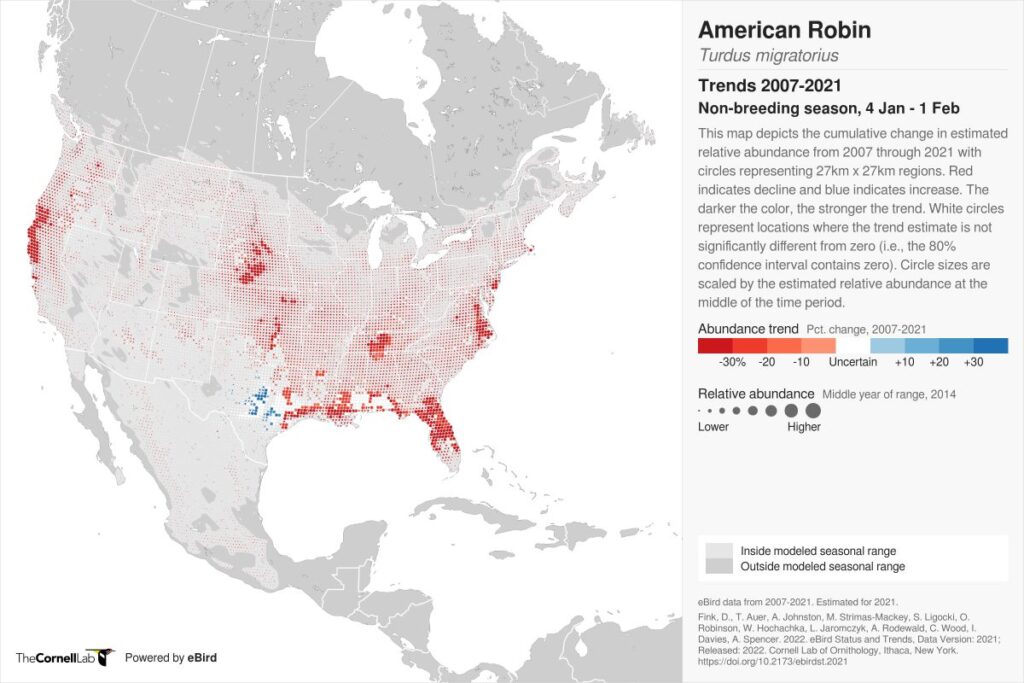

In late May boreal forest warblers such as Cape May, bay-breasted and Tennessee have reached or surpassed Tadoussac, Quebec on the way to their breeding grounds further north. They aren’t nesting yet, so if the weather turns sour they head back south temporarily to wait it out.

The weather forecast for 24 May looked promising for this perfect storm as Ian Davies (@thebirdsguy) writes in the day’s eBird checklist:

“There were southwest winds overnight (tailwinds good for migration), combined with a big cold front arriving right around dawn, bringing rain, strong northwest winds, and colder temperatures — the same setup that has resulted in flights of tens or hundreds of thousands of birds in past Mays.”

Hoping for a river of warblers, Ian and 11 others headed out to the Tadoussac dunes to count birds. In 11.25 hours they saw 263,771 birds in 96 species! Ian writes:

The first couple hours of daylight featured drizzle and strong winds, and not many birds until about 6:45 … then 500 birds/minute by 7:30. The Tadoussac river of warblers had begun.

— ebird checklist for 24 May 2023 Tadoussac

This flight continued at 300-500 birds/minute until about 9:20, at which point the rain dropped significantly, and the flood gates opened, as many as 1345 warblers/minute raging past in a torrent of flight calls and glowing songbirds. Birds were everywhere, below eye level, flying between people, pouring through the bushes, landing on the sand, and one Cape May Warbler even tried to land on my arm. A Red-eyed Vireo flew into someone. It was madness. …

For one period of time, the rate of warblers was 80,000/hour.

Here’s just one of the many videos attached to the checklist. See the checklist for amazing photos, videos and counts.

Today we saw a QUARTER MILLION warblers fly past Tadoussac, Quebec. >85,000 Bay-breasted Warblers, and >50,000 each of Cape May and Yellow-rumped Warblers. Full details, photos, and video here: https://t.co/7E1IEM1ouh pic.twitter.com/clkqS1DYAy

— TheBirdsGuy (Ian Davies) (@thebirdsguy) May 25, 2023

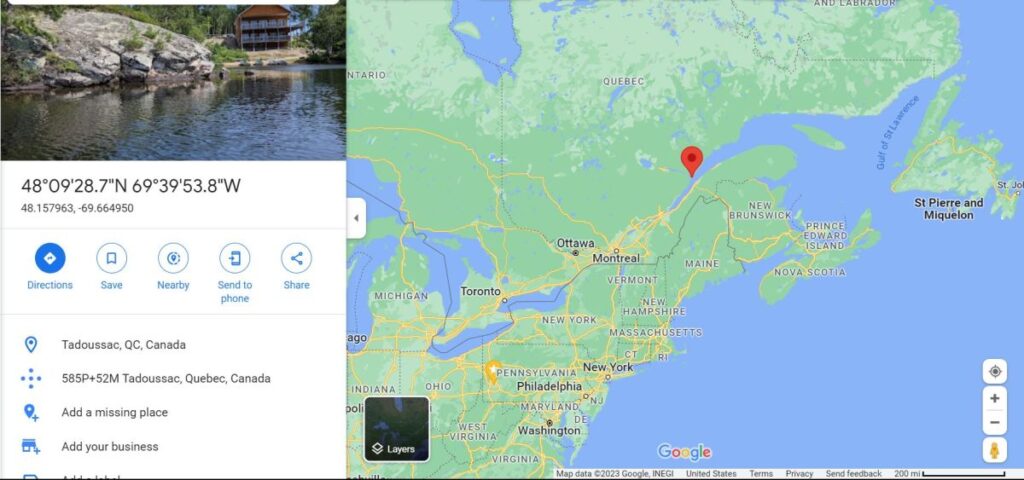

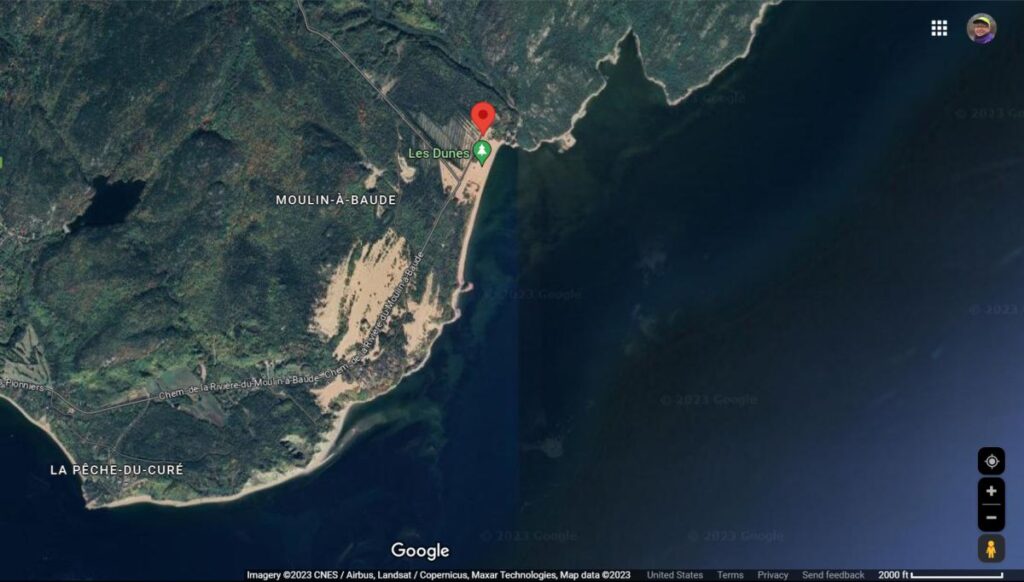

The location was key to this phenomenon. Tadoussac is located on the northwest coast of the wide St. Lawrence River which funnels birds heading south. If you look at the videos you’ll see that the cameras are pointed toward the St.Lawrence River — east/southeast — and that all the birds are flying southwest.

These birds had made it further north but when bad weather arrived they changed direction to escape the storm. Flying on the northwest wind they reached the unsheltered coastal dunes at Tadoussac so they headed southwest to the forest.

What a privilege it must have been to witness a quarter million warblers in just one day.

(maps are screenshots from Google maps; tweet embedded from Ian Davies @thebirdsguy)