16 November 2020

On my way to meet friends at Moraine State Park last Friday, I stopped to check a few coves for tundra swans. My first stop was better for bird behavior than for waterfowl. As I drove away a ruffed grouse chased my car!

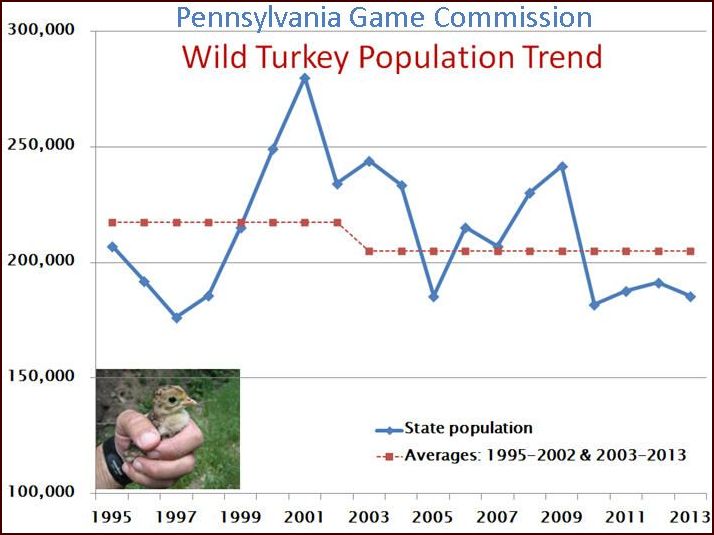

Though ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) are Pennsylvania’s state bird it had been three years since I’d seen one in the state and even then I reported the sound of one drumming in the distance, not seen. The ruffed grouse population has been declining for decades so it is rare to find one. On Friday the 13th one found me.

Naturally when I saw a grouse in my rearview mirror, flying after my car, I parked and got out to look. By then he was perched in a tree, strutting and turning his head in an apparent territorial display. I took his picture with my cellphone. He was further away than he appears.

Was he tame? Was he habituated to humans and cars? Was he stocked by the PA Game Commission?

At my next stop I told Linda Crosky and Dave Brooke about my experience. They later went to find the grouse and Dave took photos of his Life Bird (at top).

Dave also did some research and found out that, no, the PA Game Commission probably doesn’t stock them at Moraine but yes, grouse sometimes act this way. Birds like this are few and far between. They are not tame. They are hyper-territorial.

This spring PA Game Commission Ruffed Grouse Biologist Lisa Williams made a video of her visit with a so-called tame grouse. He tried to take a bite out of her.

video from PA Game Commission on YouTube

If “tame” ruffed grouse were the size of T. Rex we’d all be dead.

p.s. Want to see more? Click here for a 2017 video of a “tame” grouse approaching two men in Pennsylvania.

(photo at top by Dave Brooke; second photo by Kate St. John; video from PA Game Commission on YouTube)