13 June 2022

Some salamanders are easy to find, some are rarely seen, and some, like the green salamander, are so rare that they’re listed as Near Threatened. It was quite a surprise to find anything, let alone green salamanders, thriving in the remnants of mountaintop removal in Virginia in 2016.

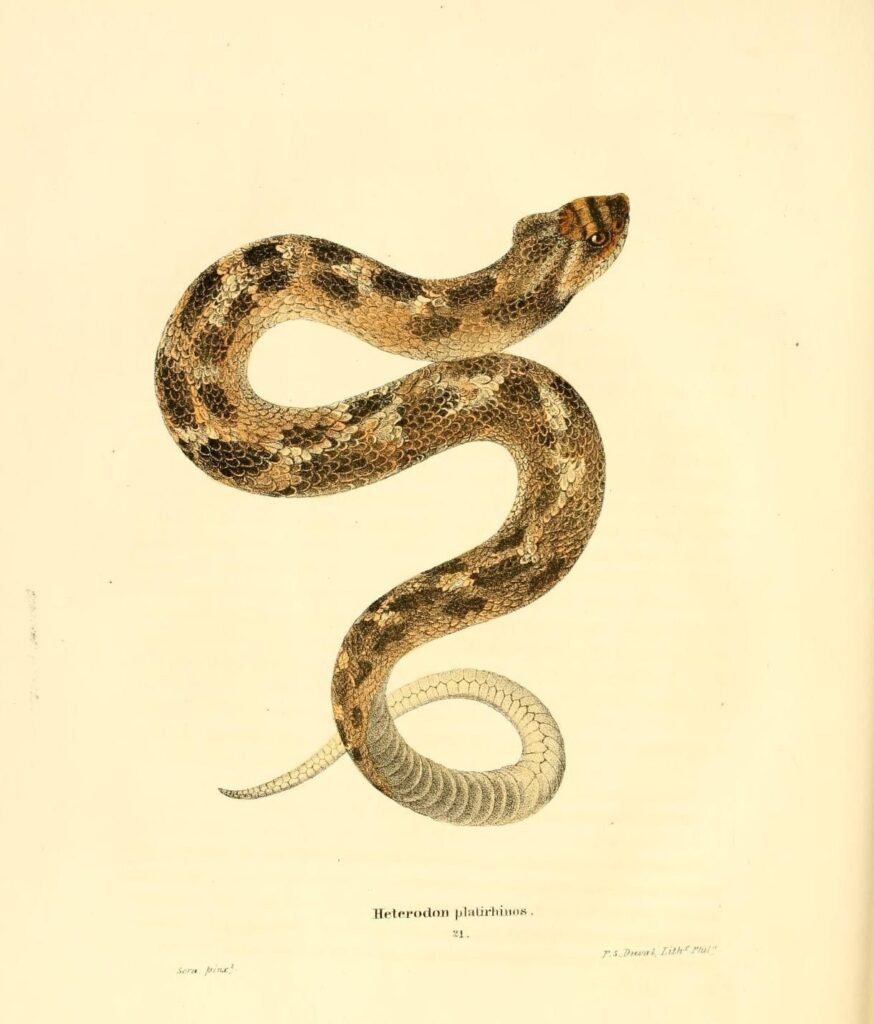

The green salamander (Aneides aeneus), native from Alabama to Pennsylvania, is a habitat specialist that lives in the dark furrows of naturally moist rock outcrops on cliffs in the Alleghenies and Cumberland Plateau.

His favored habitat is usually close to trees — he climbs them.

In April 2016 when Dr. Wally Smith of University of Virginia Wise County decided to look for salamanders at an old mountaintop removal site, he didn’t expect to find anything in the half-acre remnant of rocks and trees left by the mining company. He was stunned and overjoyed to find a green salamander.

Working with Kevin Hamed of Virginia Highlands Community College, Smith surveyed more mountaintop removal sites. There’s a lot from choose from in Wise County, Virginia.

They found that …

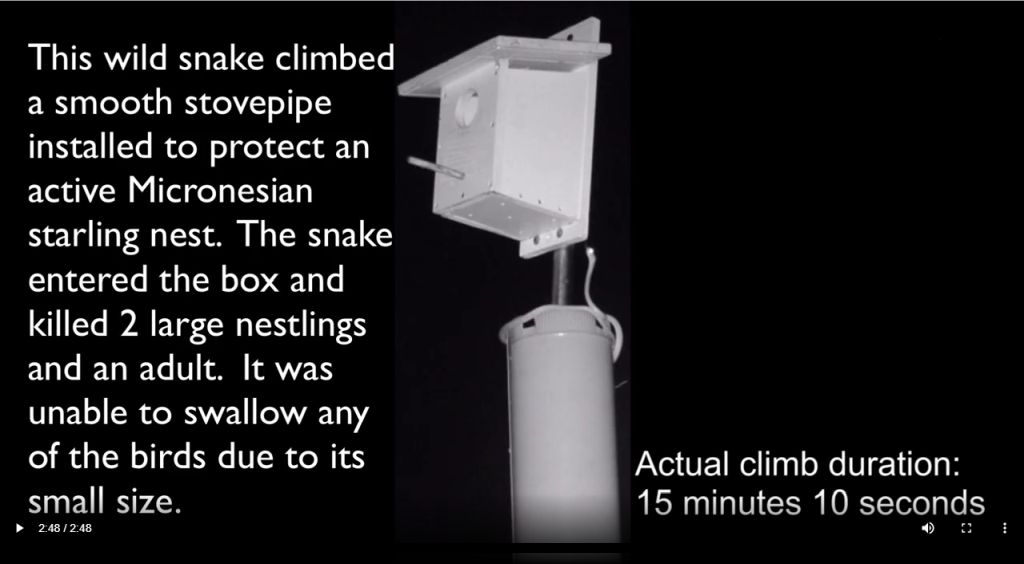

Unsurprisingly, hillsides and rock walls that had been directly carved up or deforested didn’t hold any salamanders. But around 70 percent of the surviving natural outcrops did—often in surprisingly healthy numbers. As long as the old crevasses and tree-cover were present, the species showed up, regardless of the racket and disturbance nearby. “The salamanders in these pockets seem to be doing pretty well,” Smith said. “They’re abundant, they’re reproducing, which are signs that the populations are still hanging on.”

— Gizmodo: Rare Appalachian salamanders are reclaiming abandoned Coal Mines

The discovery led to more questions so Smith and Hamed expanded their search and, with the help of locals and landowners, found 70 locations with salamanders including …

… a motherload of salamanders in the municipal park of a local city. “Usually if you’re lucky, you find one or two a day. There, we were finding 70 to 100 per hour,” said Smith.

— Gizmodo: Rare Appalachian salamanders are reclaiming abandoned Coal Mines

This photo of Kayford Mountain, WV gives you an idea of the remnant pockets the mining companies leave behind.

How did green salamanders get to these sites? Is each site a remnant “island” population or do the groups interchange with populations elsewhere? The study continues.

Meanwhile it’s a miracle to find them at all.

Read more about the salamanders at mountaintop removal sites in Gizmodo: Rare Appalachian salamanders are reclaiming abandoned Coal Mines.

Learn more about mountaintop removal before-and-after at Appalachian Voices.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons, Virginia Division of Mined Land Reclamation and Rana Xavier via Flickr)