4 October 2023

Joe, Sam and Jared joined me yesterday morning on an adventure to see Bird Lab at Hays Woods. The weather was perfect as we walked more than half a mile to the banding station. There we found Nick Liadis and his assistants about to do the second net-check of the day.

The mist nets that capture songbirds are set up in “alleys” of vegetation where birds might fly across. If a bird doesn’t see the net and tries to fly through, it falls into the pocket of extra netting material where it waits to be retrieved. Banders check the nets every half hour.

Captured birds are brought back to the banding table in cloth bags to keep them calm. Our group watched as Nick prepared to band three birds from the recent net check.

Each bag contains a surprise. The first was a recaptured Cape May warbler (Setophaga tigrina), originally banded on 20 Sep when it weighed 10.9g. Yesterday it weighed 13.8g for a gain equivalent to the weight of a ruby-throated hummingbird. Such a small bird in Nick’s hand, below.

It was the second Cape May warbler recapture this fall. The first one increased its weight by 50% in two weeks. About the first one, Nick wrote:

A cool recapture from my Hays Woods banding station! This Cape May Warbler was banded on 9/13 and we captured her again two weeks later. She originally weighed 11.6g and today weighs 15.4g. Interesting to see how long some of these birds hang around. I’d imagine she’ll be on her way very soon.

— Nick Liadis message, 27 Sep 2023

Next on the agenda was a hatch year (meaning “hatched this year”) male black-throated blue warbler (Setophaga caerulescens). His color was blue, but not vibrantly so, and his throat had tiny white flecks on it. I had seen a dull bird like this in Frick Park last week and didn’t realize that meant he was young.

At each successive net check new species showed up.

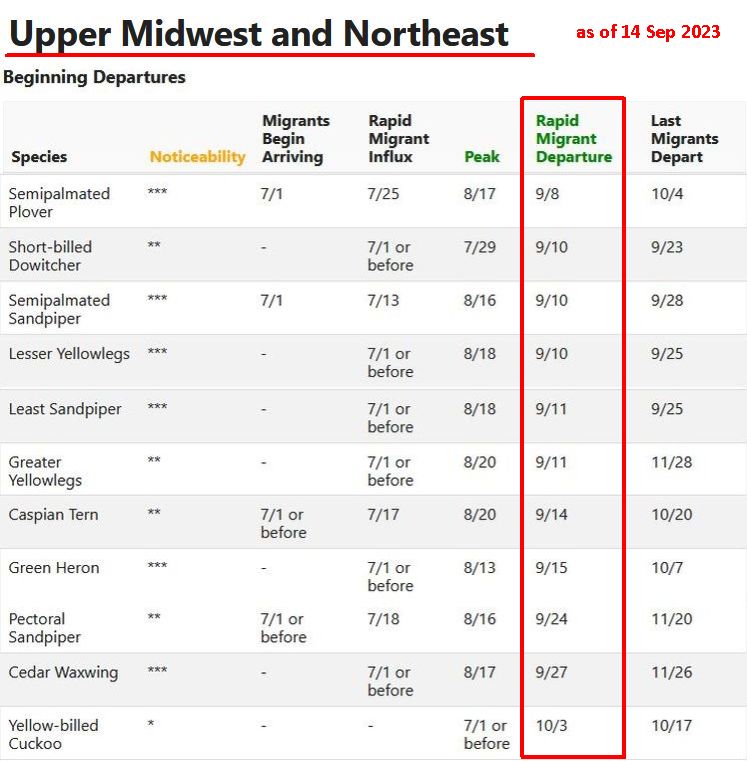

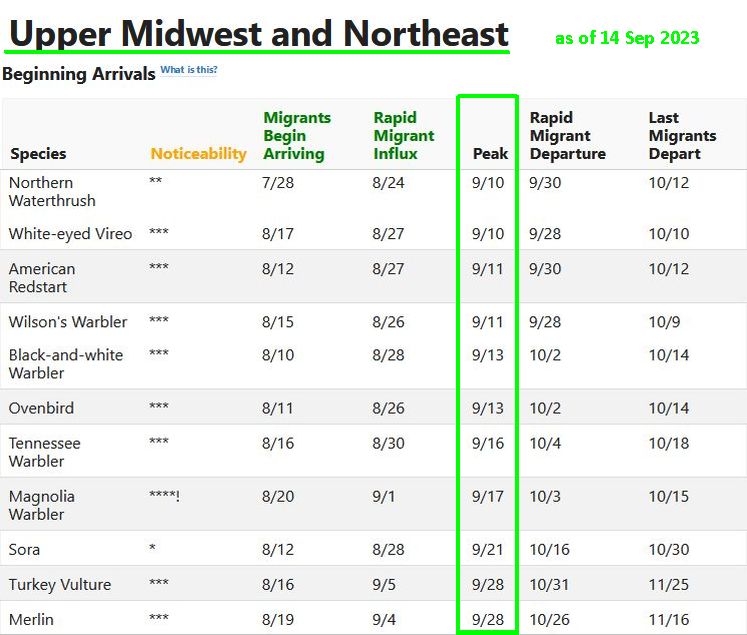

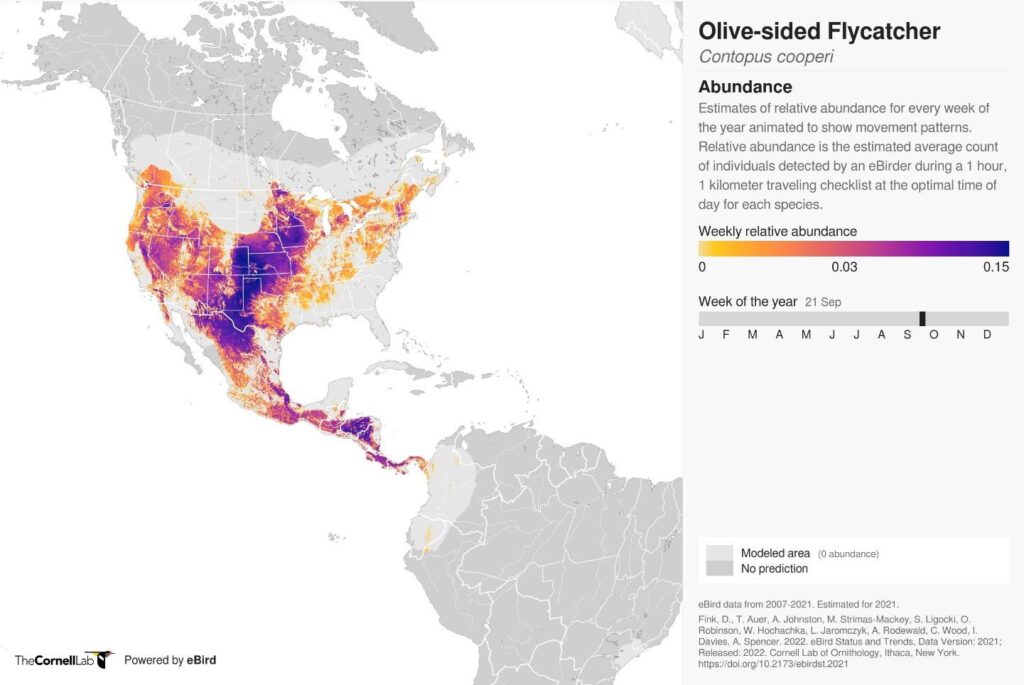

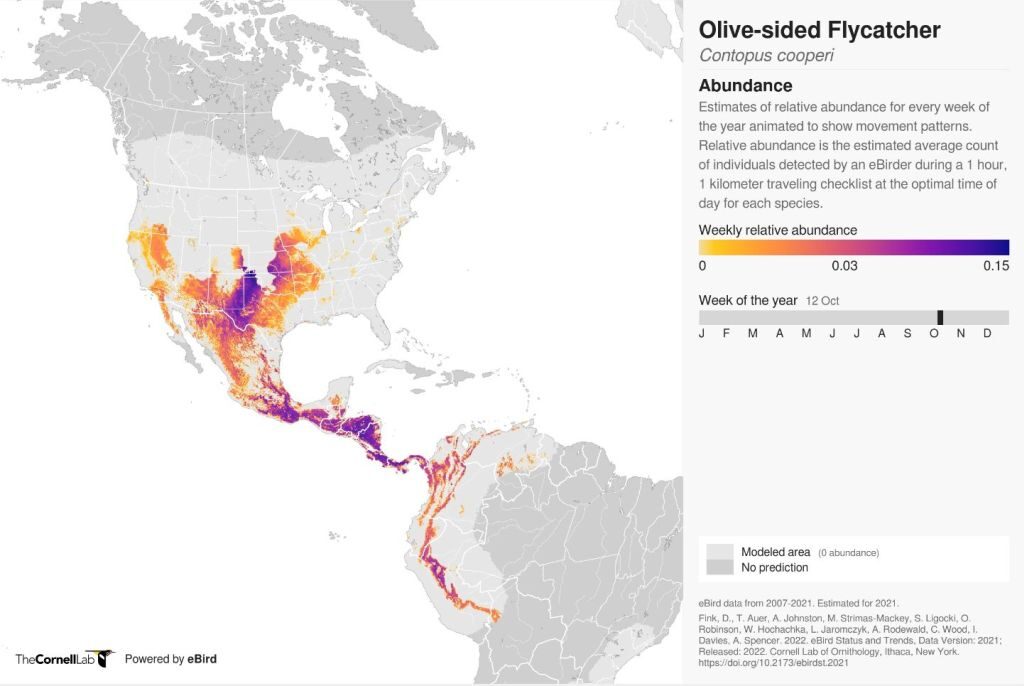

The hatch year hermit thrush (Catharus guttatus) shown at top was a sign that the mix of migrant species is changing. The insect eaters are nearly gone while the fruit and nuts migrants have arrived (*see note).

The hatch year female house finch, below, was probably born at Hays Woods. Many house finches in the eastern U.S. are permanent residents. Perhaps she will be, too.

An ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla) is always nice to see up close and I had no trouble identifying it because it showed its striped crown. I saw one in the hand at Bird Lab last year.

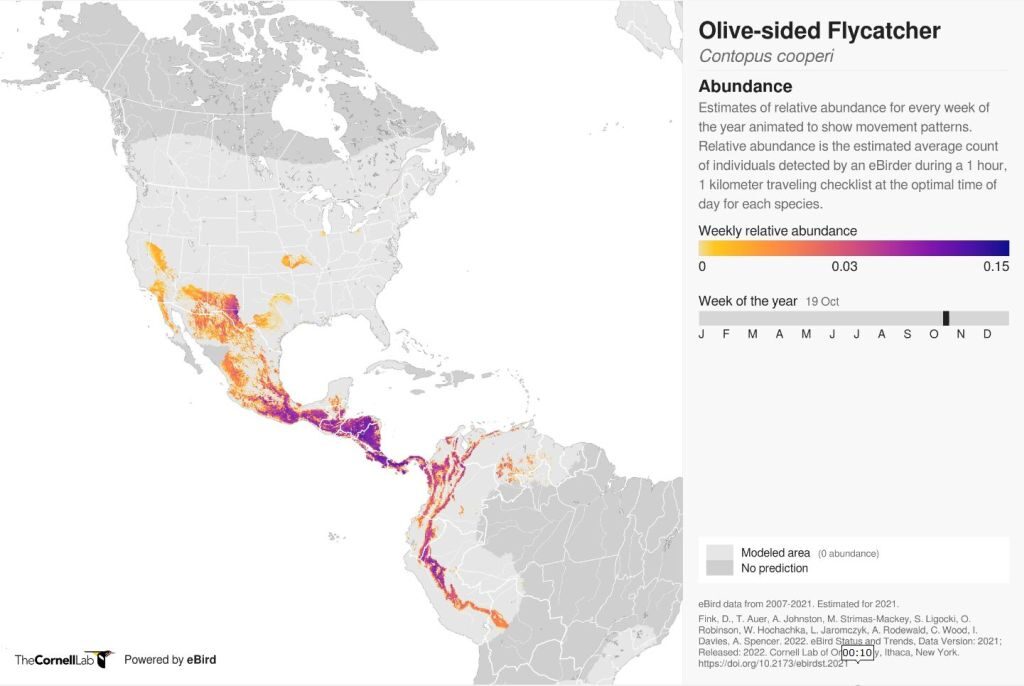

By 10:00am we’d been there an hour, it was getting hot (the high yesterday was 85°F!) and the birds were less active. Three of us hiked to the overlook and returned for one more net-check. This time only one bird was captured, a hatch year house wren (Troglodytes aedon) that Nick had banded on 9 August. This bird has spent the last two months foraging at Hays Woods and soon it will migrate to Central or South America.

We left Bird Lab and headed back to the parking lot where the fleet of enormous dump trucks, seen at 8:30am, were still shuttling dirt to/from Duquesne Light’s dirt road. Duquesne Light is building an access path to the cliff edge where two transmission towers need to be replaced and moved away from the landslide zone.

Thanks to Jared Miller for sharing his photos, shown above.

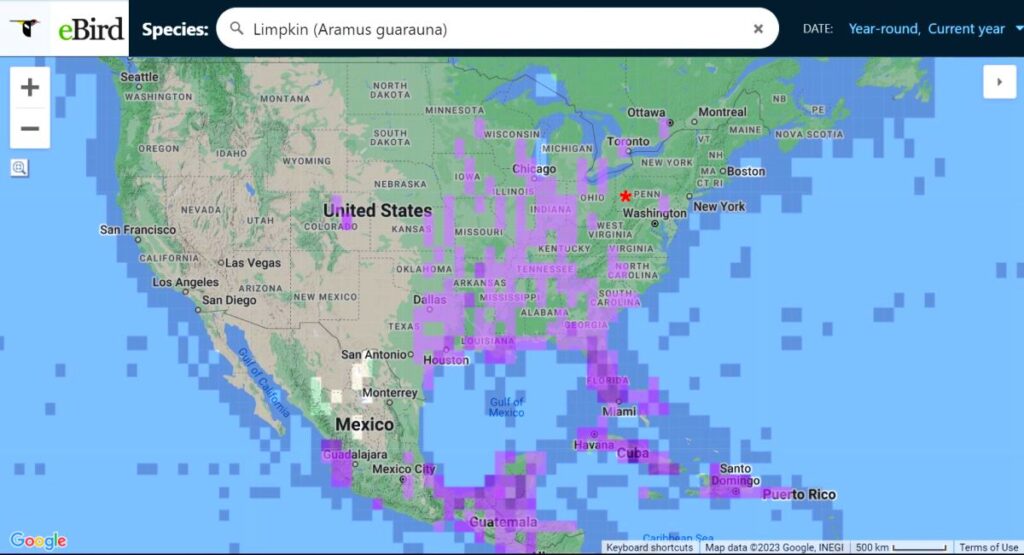

Bonus Bird: After the banding, a rare bird at Duck Hollow:

At 10:30am I received an alert that a migrating American avocet (Recurvirostra americana) was hanging out at Duck Hollow. Avocets in Allegheny County are One Day Wonders. I had never seen one here because I waited a day to go see them. So I made the short trip from Hays Woods to Duck Hollow and digiscoped this lousy picture. The light was too bright to see its faint orange color but you get the idea.

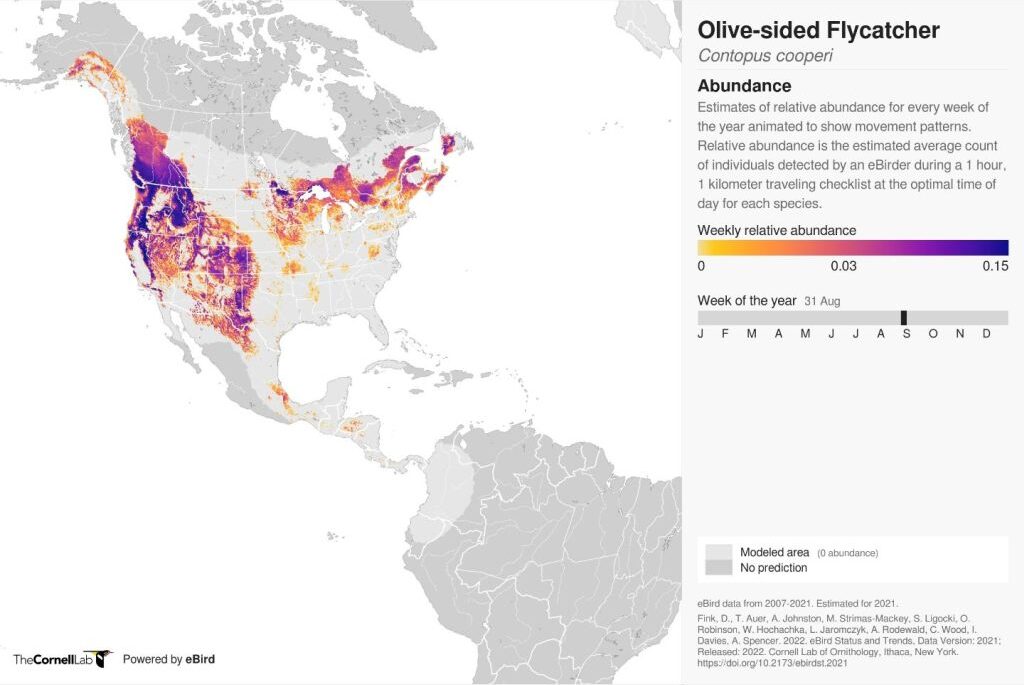

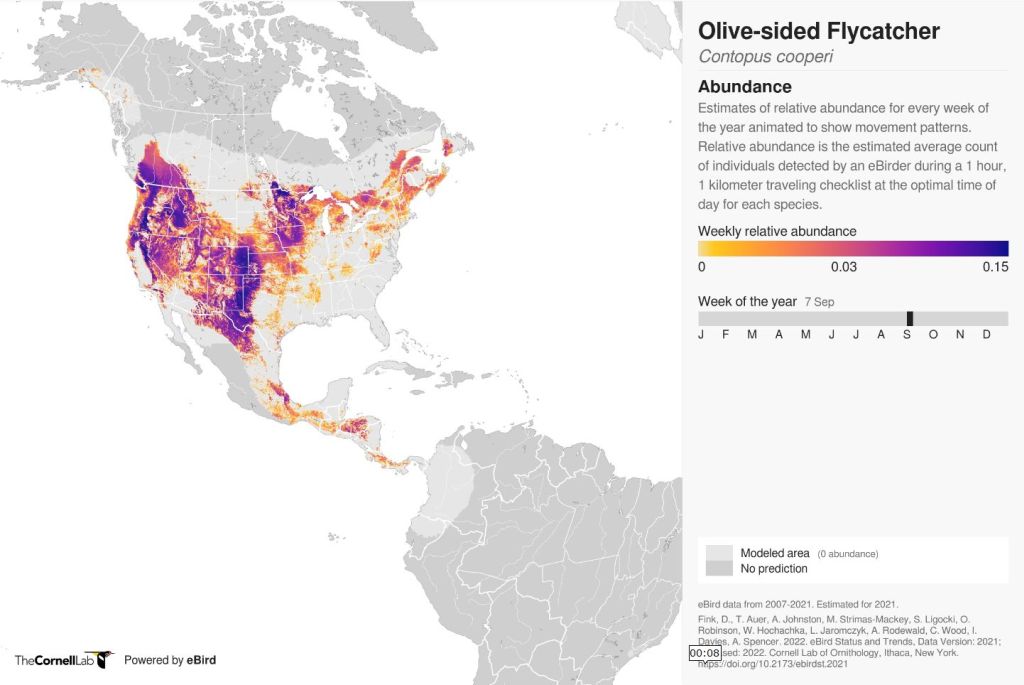

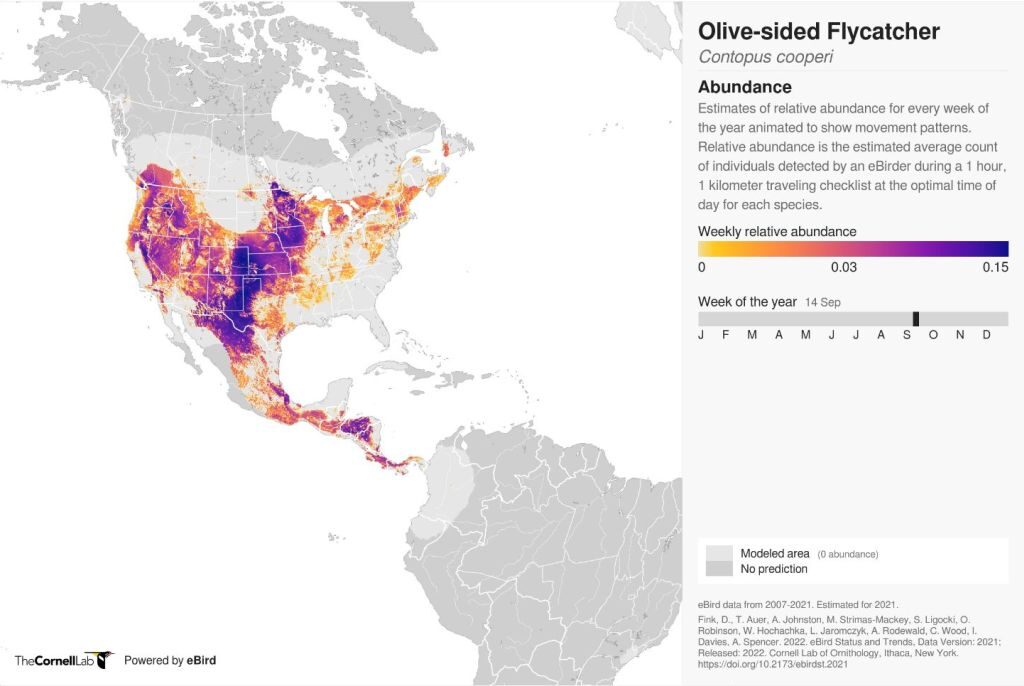

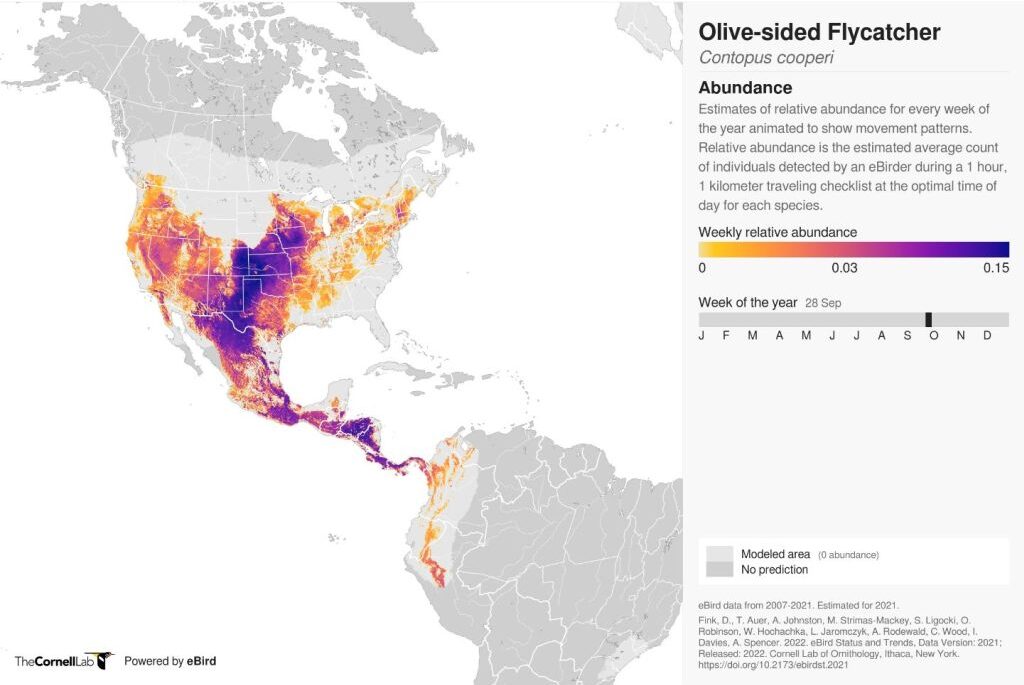

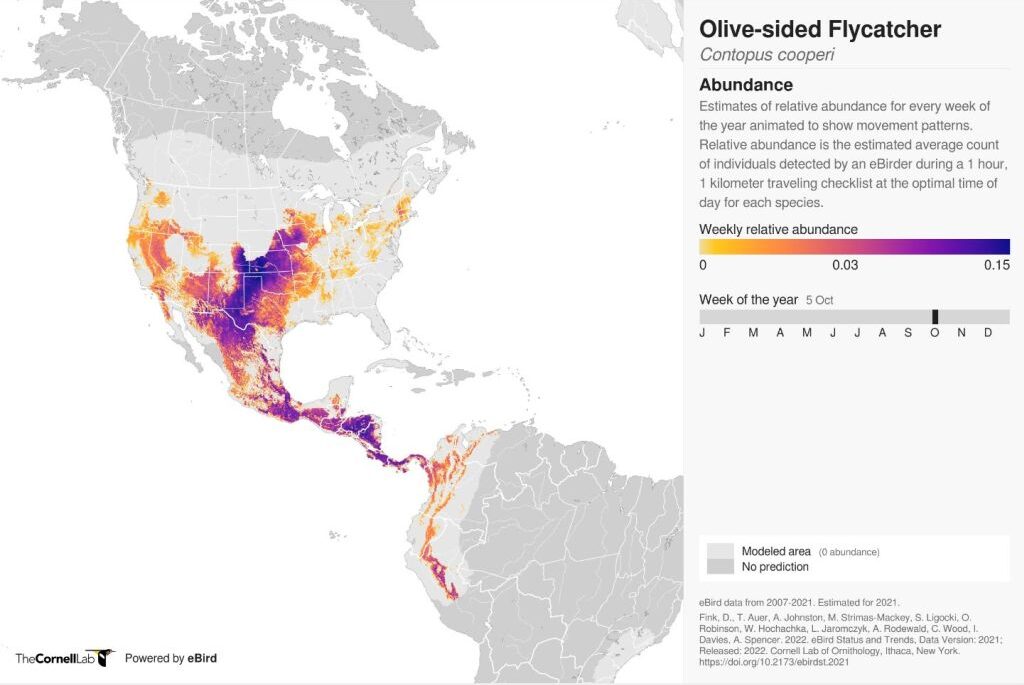

p.s. (*) Two of the phases of fall migration: ** Insect eaters such as warblers, flycatchers, swifts and swallows migrate through in September because the bug population is going to die when cold weather hits. ** Fruit and nut eaters, including thrushes and sparrows, pass through in October.

(photos by Jared Miller and Kate St. John)