Here we are – on our way to Acadia National Park.

Here we are – on our way to Acadia National Park.

Back in 1983 my husband and I didn’t imagine we’d love Maine so much that we’d come back to Acadia every year. Now on our 25th visit it’s like coming home. We’re “regulars” at the Harbourside Inn where we’re welcomed like family and catch up with the many friends we’ve made over the years.

We’ve seen every kind of weather from sunny and cool to a week of dense fog. The only awful time was The Year of Four Hurricanes when the remnants of Edouard, Fran, Gustav and Hortense brought one rain storm after the other. It’s a mighty good record that we had to spend our vacation indoors only once.

For a birder and hiker like me, Acadia is paradise. There are woodland, seaside and mountain trails, views of the ocean from every angle and groomed carriage paths for bicycling, horseback riding and easy walking. Canoeing and kayaking are popular on the lakes, sea kayaking on the ocean.

September is migration time for many birds. When the wind’s from the north I visit the Acadia Hawk Watch on Cadillac Mountain. When the weather’s rainy I sometimes encounter a warbler fallout – tiny birds feeding just an arm’s length away – because the weather forced them to land.

Last year I went on a Whale Watch and I saw a “life bird” from Antarctica: a south polar skua. And I always find a peregrine falcon somewhere on the island, either at the Hawk Watch or on one of the seaside cliffs. Several pairs of peregrines nest on the island, though nesting season is long over by the time we arrive.

Sometimes people ask me, “How can you vacation at the same place every year?” True, it reduces our ability to travel widely but our time at Acadia is so restful that we won’t give it up. The highest accolade we can give to a day is to say, “It’s just like Maine.”

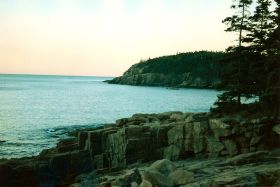

(I took this photo of Otter Cliff many years ago.)

I don’t think of August as a time when peregrines do any courting so it was with some surprise that I found this webcam photo yesterday.

I don’t think of August as a time when peregrines do any courting so it was with some surprise that I found this webcam photo yesterday.  After a long, long spate of beautiful weather we now have a drought. The sunny days and clear cool nights I find so appealing have not produced any rain. It’s another case of too much of a good thing.

After a long, long spate of beautiful weather we now have a drought. The sunny days and clear cool nights I find so appealing have not produced any rain. It’s another case of too much of a good thing. The

The