Last weekend two pieces of a puzzle came together for me. I saw an endangered turtle and I read a thoughtful book, The Value of Species, that describes how our values shape his plight.

The wood turtle is approaching extinction because of bulldozers and collectors — habitat loss and the pet trade. He’s one of many species in this human-induced predicament. In fact so many species are declining now that scientists say we’re heading into a great extinction, perhaps on the scale of the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event that killed the dinosaurs.

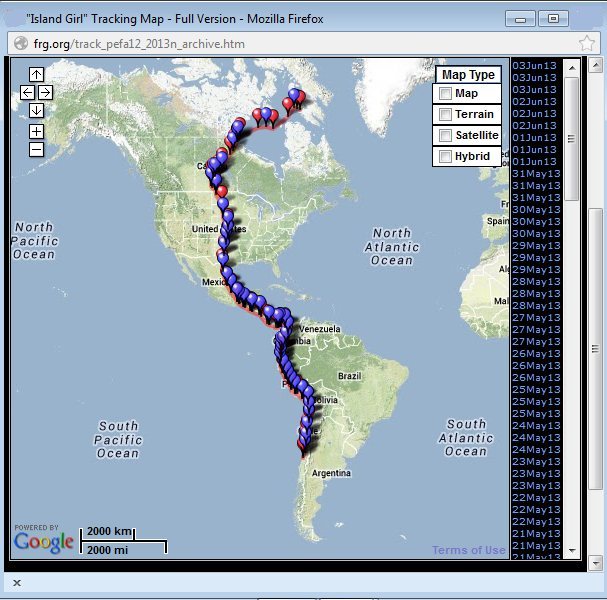

Our actions cause decline and extinction yet we continue to do them. We’ve saved some species like the peregrine falcon with spectacular results but our overall track record is poor. New problems arise faster than we can stop them. Why?

In The Value of Species, Edward L. McCord explains that our values get in the way.

- Human population growth is crowding out other species but we avoid thinking about our role in this problem.

- We gladly protect an individual animal from harm but find it hard to protect an entire species.

- We understand the monetary value of species but not their intrinsic value.

- It’s hard for us to connect the need to save habitat (land) in order to save species.

- Protections on land owned by the state for the common good can be trumped at the state level. (The book discusses mineral leases on national land in Mongolia. Marcellus leases in Pennsylvania’s State Forests is an example close to home.)

- The common good erodes easily when people don’t trust that others will obey the rules. When a society lacks trust species are vulnerable.

Chapter Three, The Fate of Life on Earth Hinges on Property Values, is especially apt this week. On June 25 the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Koontz v. St. John’s River Water Management District made it harder for the common good of living things to compete with property values.

The short time span of property ownership is microscopic when weighed against species who’ve been on earth for two million years and could disappear in a matter of decades. “Still, many people are inclined to give individuals the right to reduce the living heritage of the earth for all future generations no matter how briefly they own a piece of property — even if only for a week.”(1)

McCord describes a new and deeper way to see the intrinsic value of all species. When we do, we can change the trajectory of extinction by “drawing a line in the sand, something we do all the time to protect important values.”(2)

What will be the fate of the wood turtle? The Florida grasshopper sparrow? The red-breasted goose?

Ed McCord’s The Value of Species shows us the way to a brighter mutual future.

(photo of a wood turtle from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the image to see the original.

Quotes from The Value of Species (1)page 51, (2)page xvii

Edward McCord is the Director of Programming and Special Projects at the University of Pittsburgh’s Honors College)

p.s. Ed McCord gave a talk about the book at the University of Wyoming in April 2014. Click here for the video.