For a bird that eats fish for a living, what possible advantage could there be in having feathers that get waterlogged?

Water beads up on the plumage of ducks and loons but the feathers of double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) are “wettable” so they spend more than half their day out of the water loafing, preening and spreading their wings to dry as shown in the video above(*).

This wettability is not caused by a lack of oil on their feathers. Instead it’s the feathers’ structure that allows them to get wet.

Combined with their solid, heavy bones, wettable feathers make cormorants less buoyant so it’s easier to stay underwater and hunt for fish.

The proof is in the eating. Ta dah! He caught a large catfish.

Double-crested cormorant with fish, Everglades National Park (photo from Wikimedia Commons)

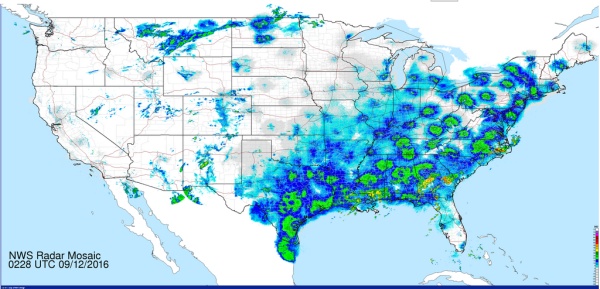

Watch for double-crested cormorant numbers to build in western Pennsylvania this fall as they migrate south for the winter.

p.s. *Note: The bird in the video has a white feather or debris on top of his beak. It’s not a field mark.

(video from Cornell Lab of Ornithology, photo by R. Cammauf, National Park Service, via Wikimedia Commons. Click on the image to see the original.)