Connecticut warblers are rarely seen on migration and it’s not just because they skulk in dense underbrush. A study published last May in Ecology shows they have a very unusual migration route.

McKinnon, Arturo and Love attached geolocators to 29 male Connecticut warblers in Manitoba in 2015, then recaptured four of them the following spring when they returned to breed. The data from the geolocators shows the four birds followed similar routes to their wintering grounds in South America.

After flying east to the Atlantic coast with stopovers along the way each bird launched out over the open ocean and flew two days non-stop to the Greater Antilles, probably Haiti. After refueling in the Caribbean they flew again over the ocean to South America and the Amazon basin.

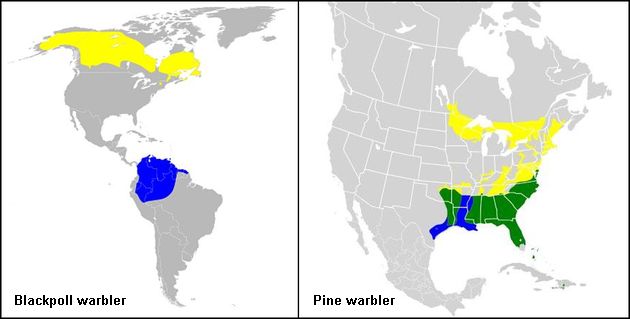

To give you an idea of this feat I drew a very rough map based on my reading of the study. This map is not the real thing! Click on the image to see one of the actual maps or here for all four.

With two long flights over open water, no wonder we don’t see many Connecticut warblers in migration.

If you’re really lucky you might see one this month in Pennsylvania. Otherwise you’ll have to wait until next year.

(photo by Steve Gosser . map adapted from satellite image of the world at Wikimedia Commons)

p.s. Additional information about the study is here at Bird Watchers’ Daily.