8 December 2023

If you live in Central America you may find this bird on your front porch.

Happy Friday!

8 December 2023

If you live in Central America you may find this bird on your front porch.

Happy Friday!

6 December 2023

The Nutty Series: Buckeyes are the Aesculus genus

Buckeyes have always been one of my favorite objects because their skin is smooth and shiny fresh out of the husk, perfect to carry in my pocket like a worry stone.

In America, the native Aesculus are commonly

— Arboretum FOundation (in Seattle): The Many Faces of Aesculus

called “buckeyes,” a name derived from the

resemblance of the shiny seed to the eye of a

deer [a buck’s eye]. In the Old World, they’re called “horse

chestnuts”—a name that arose from the belief

that the trees were closely related to edible

chestnuts (Castanea species), and because the

seeds were fed to horses as a medicinal treatment for chest complaints and worm diseases.

In Pittsburgh we call all of them “buckeyes.”

Let’s go backwards in the growing season from nut to husk, flower and leaf by examining buckeyes planted in Schenley Park more than 100 years ago.

The large nut pictured at top left is from a European horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) native to Albania, Bulgaria, mainland Greece and North Macedonia. Each husk contains one to three nuts. Sometimes they’re flat on one side. My favorites are the round ones.

On the tree, horse chestnut husks are spiny.

They’re produced from the white flowers that have pink (already fertilized) highlights. Notice that each leaf has seven fat leaflets. The number and shape of the leaflets indicate this is a horsechestnut.

In winter horse chestnuts are easy to identify by their large, sticky end buds.

The yellow buckeye (Aesculus flava) is native to the Appalachians and Ohio Valley and is North America’s tallest buckeye tree at 70 feet. Planted as an ornamental in Schenley Park it can hybridize with its shorter cousin, the Ohio buckeye (Aesculus glabra), making identification difficult for non-botanists like me.

Yellow and Ohio buckeye nuts look a lot like horse chestnuts. Seeing the husk is a big help because yellow buckeye husks are smooth …

… while Ohio buckeye husks are slightly spiny. The narrow leaves also indicate a native buckeye. (Yes, the leaves looked sick that year.)

Their flowers are pale yellow (not white) and narrower than the horse chestnut’s. (*)

Yellow buckeye buds are large but not sticky. They’re one of the first to leaf out in the spring.

Ohio buckeye buds are strongly keeled.

For a summary of nine common buckeyes (Aesculus) used in landscaping see The Spruce: What is a Buckeye?

p.s. The small buckeye nut in the top photo is from the shrub-sized bottlebrush buckeye (Aesculus parviflora), planted in Schenley Park near Panther Hollow Lake. Click here to learn more.

(*) Which Flowers? I could not tell whether the flower photo was yellow or Ohio buckeye. Mary Ann Pike suggests Ohio buckeye in this comment.

29 November 2023

Last month shagbark hickories (Carya ovata) put on a show in Pittsburgh’s parks with bright yellow leaves and fallen nuts.

The thick green husks began to turn brown immediately and peel off in quarter-moon sections. This piece of husk sat indoors for more than a month before I took a photo of its interior. The dark brown exterior is visible at the bottom edge.

If a nut lasts through the winter its husk looks quite worn out by March. This one was probably uneaten for a good reason.

Shagbark nutshells are slightly oval with a remnant stem and four ribs. When I cracked open the nut I collected, it was a dud. Maybe an insect got to it. This Wikimedia photo of a sawed nut shows the meat.

Though shagbark hickory nuts taste good and can substitute for pecans, shagbarks are not cultivated because …

They are unsuitable to commercial or orchard production due to the long time it takes for a tree to produce sizable crops and unpredictable output from year to year. Shagbark hickories can grow to enormous sizes but are unreliable bearers.

C. ovata begins producing seeds at about 10 years of age, but large quantities are not produced until 40 years and will continue for at least 100. Nut production is erratic, with good crops every 3 to 5 years, in between which few or none appear and the entire crop may be lost to animal predation.

— Wikipedia Shagbark Hickory account

Interestingly, shagbarks (Carya ovata) and pecans (Carya illinoensis) can hybridize in the wild though the hybrids usually don’t produce nuts.

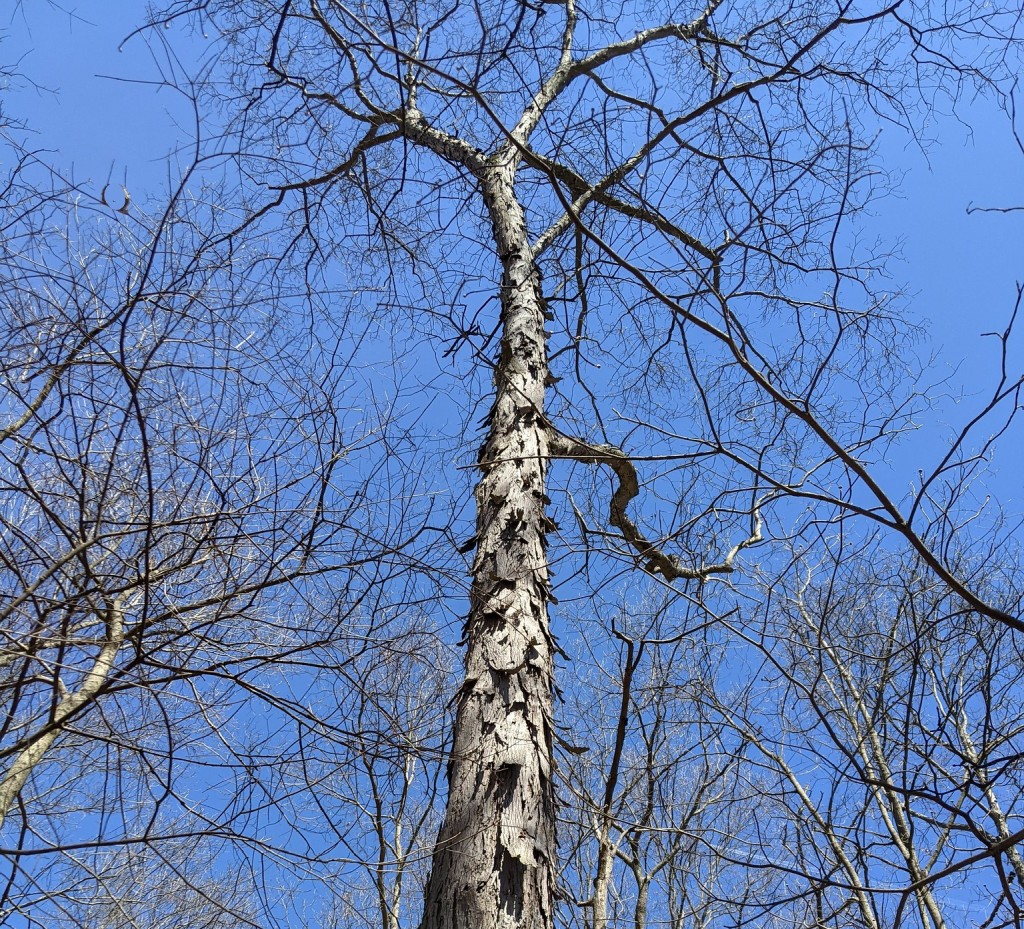

Shagbark hickories are easy to identify by their shaggy bark. Just look up and you’ll see it peeling from the trunk. Young trees can fool you, though, because they have smooth bark (click here to see young bark).

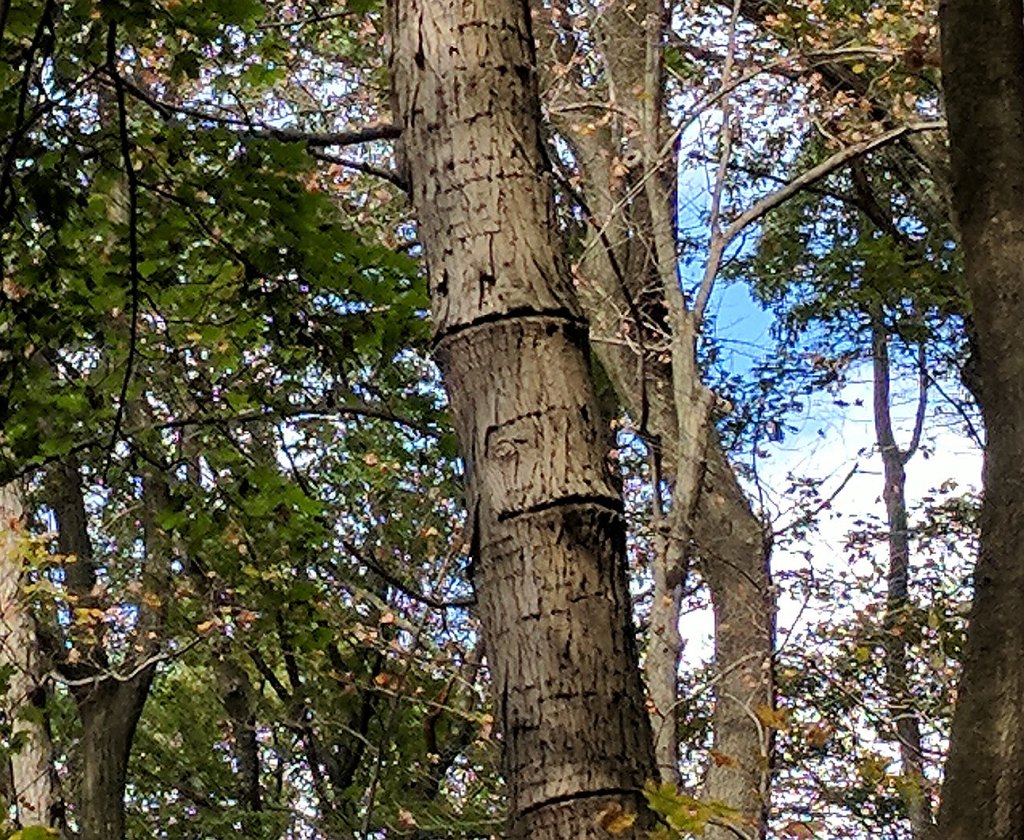

Shagbarks are one of the first native trees to leaf out so their sap runs early in the spring. Yellow-bellied sapsuckers (Sphyrapicus varius) take advantage of this and drill the trees as they migrate north. The birds move sideways around the trunk as they drill in a ring around the tree. The trees heal the wounds by producing callus tissue that grows outward, almost like lips. These attract the the sapsuckers who then drill the same rings year after year.

(credits are in the captions)

22 November 2023

Black walnut trees (Julgans nigra) are common in the Pittsburgh area. Their nuts are always ready to eat in time for the holidays.

In September the fruit was still on the trees while we searched for fall warblers among the leaves.

By the end of October the fruit had fallen and started to look bruised. Eventually the husks turned black.

But most black walnuts aren’t abandoned that long. Squirrels gather them for winter food and eat a few along the way.

Squirrels know that they have to open the shell on both sides to get all of the nut meat.

The meat does not come out easily! It usually breaks into small pieces on the way out and is never the perfect shape of grocery store walnuts.

The ones we buy in the grocery store that are grown in California are English walnuts (Juglans regia) which would not be possible without the life-giving participation of black walnut trees (Julgans nigra).

Non-native English walnuts are susceptible to root diseases in California so walnut farmers plant native black walnut trees to start the orchard. When the black walnuts are a year old with strong roots and vigorous base they are chopped off and an English walnut shoot is grafted to the stump.

All the trees in the orchard below show the wider stump base (highlighted in yellow) that ends at the graft point. Above the graft English walnuts produce their own delicious nuts which are harvested after they fall by sweeping and vacuuming from the ground. FLORY harvesting equipment is pictured below.

Black walnut trees can be identified in winter as a bare tree standing alone with twigs that have alternate (not opposite) small buds above large leaf scars.

Black walnut trees stand alone because …

Like other walnuts, the roots, inner bark, nut husks, and leaves [of Julgans nigra] contain a nontoxic chemical called hydrojuglone; when exposed to air or soil compounds it is oxidized into juglone that is biologically active and acts as a respiratory inhibitor to some plants. Juglone is poorly soluble in water and does not move far in the soil and will stay most concentrated in the soil directly beneath the tree.

Symptoms of juglone poisoning include foliar yellowing and wilting. A number of plants are particularly sensitive. Apples, tomatoes, pines, and birch are poisoned by juglone, and as a precaution, should not be planted in proximity to a black walnut.

— quote from Wikipedia

(credits are in the captions)

18 November 2023

After beautiful fall foliage in late October, the landscape faded to brown this week. All the colors were in the sky.

Friday’s sunrise was spectacular for good reason. “Red sky at morn” meant rain was on the way. Fortunately. Even with yesterday’s precipitation we are 6.81 inches below normal for the year.

Wednesday’s sunset was muted by comparison.

By now the native trees in Pittsburgh are all brown or bare, so why are there still yellow and green leaves in Schenley Park?

Invasive alien plants are tuned to the climate and daylight levels of their homeland. Those that originated further north than Pittsburgh, Japan for instance, see our November daylight as if it were October back home. Thus invasive honeysuckle bushes are still yellow-green and Norway maples still cling to their yellow leaves.

This virburnum retains its pinkish-green leaves for the same reason.

The sun’s low angle showed off two Agaricaceae mushrooms among fallen leaves in Hays Woods.

Yesterday I found a tree on stilts in Schenley Park. This black locust germinated on top of a log on a rock. As the log deteriorated the roots found soil on either side of the rock. Years later there is a significant gap between the trunk and the ground.

(photos by Kate St. John)

15 November 2023

Different species of hickory nuts look the same … but not quite. This one, partially in its husk, was a puzzle so I brought it home. Husks and shells together provide the clues so I had three nuts to work with in various stages of undress, plus a table of southwestern PA hickory husk and shell characteristics.

| Common Name | Scientific name | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Shagbark Hickory | Carya ovata | Nearly round, 1.75", thick, green, splits to base | Nut has 4 ribs |

| Mockernut hickory | Carya tomentosa | Oval to pear shaped, 1.75", green, husk is thinner than shagbark's, splits to base | Nut is thick-shelled with 4 ribs |

| Pignut hickory | Carya glabra | Oval or slightly pear shaped, 1.5", thin husk green to tan, maturing to da rk brown, usually splits only partway to base | Nut has no ribs |

| Bitternut hickory | Carya cordiformis | Very thin rough husk with 4 wings, splits only to the middle as if it is peeling off the shell | Nut is round, small and thin-shelled with a pointed tip |

The Verdict: The photo was taken after the nuts sat indoors for three weeks. The husk is still pear shaped but has turned brown and splits completely. Hmmm. The nut, however, has no ribs so I’d say this is a pignut.

Sliced open it would look like this. I lack the tools to make such a clean cut.

Pignuts were too bitter for European settlers so they fed them to their pigs, hence the pignut name. However pignuts are prized by wildlife including chipmunks, squirrels, mice, blue jays, red-bellied woodpeckers and wild turkeys. If deer eat them they will soon disappear from the ground in Pittsburgh’s parks.

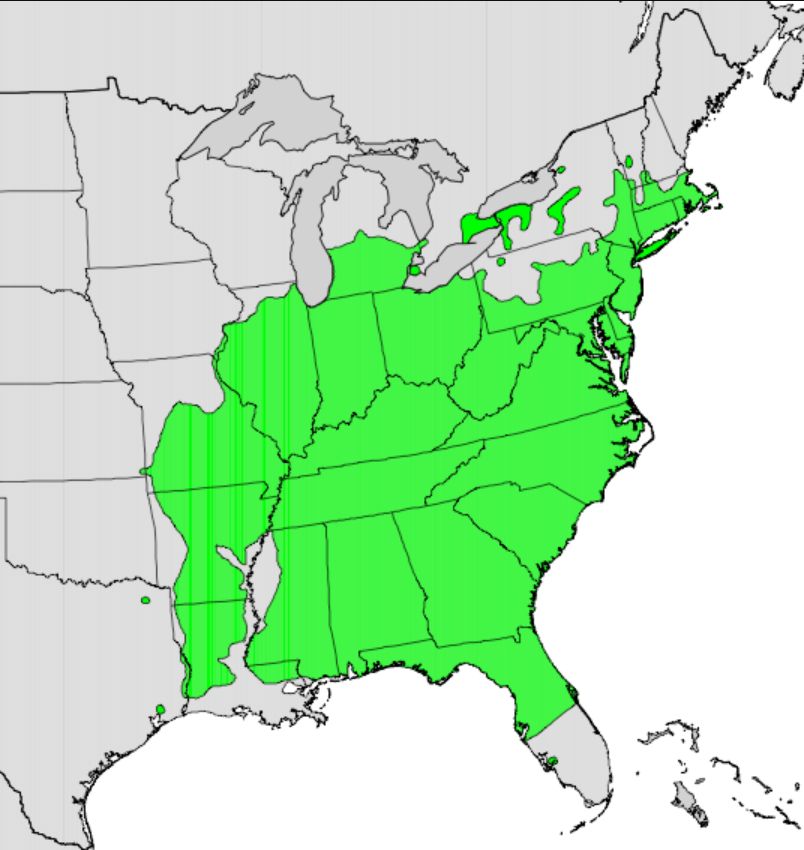

Pignut hickories (Carya glabra) range along the east coast (the original colonies) all the way to the Mississippi Valley and down to the Gulf of Mexico but don’t normally grow in northern Pennsylvania.

In winter they are best identified by their buds. As with all hickories, the end bud is larger than the side buds but on the pignut it is relatively small and the side buds are almost at right angles to the twig. This one is about to burst into spring leaves.

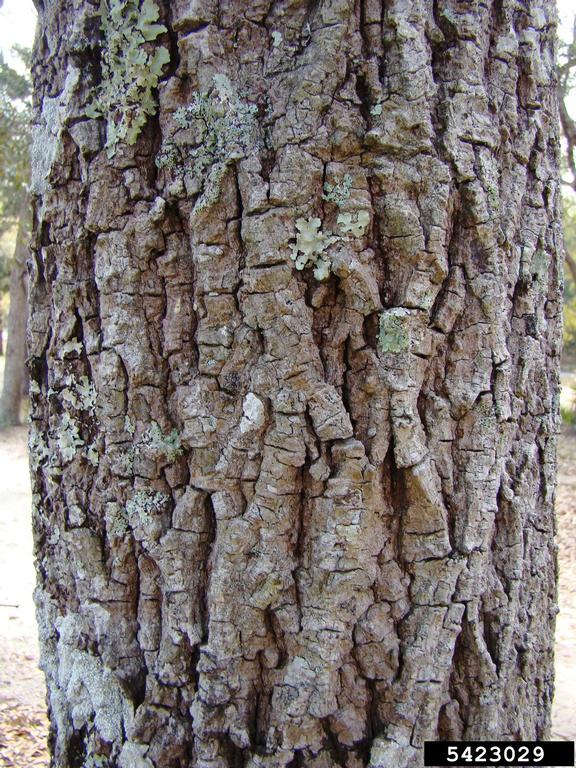

Young trees have smooth bark. Mature ones have these ridges.

The tree’s compound leaves have 5-7 serrated leaflets …

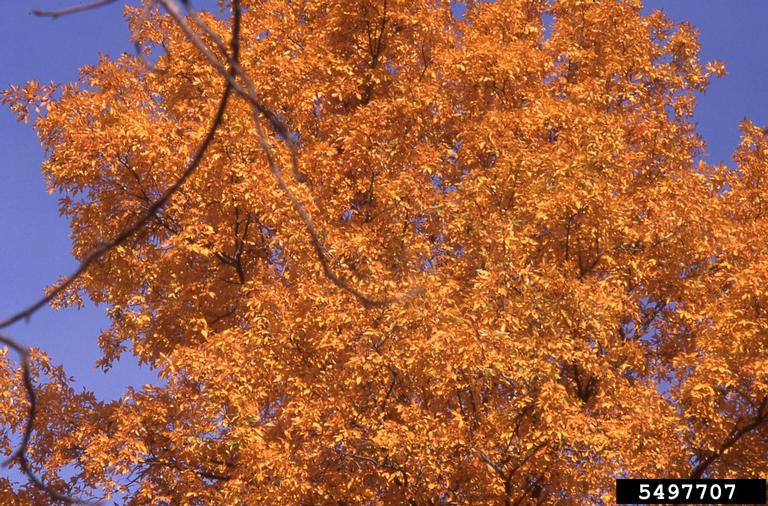

… which turn a beautiful golden color in the fall.

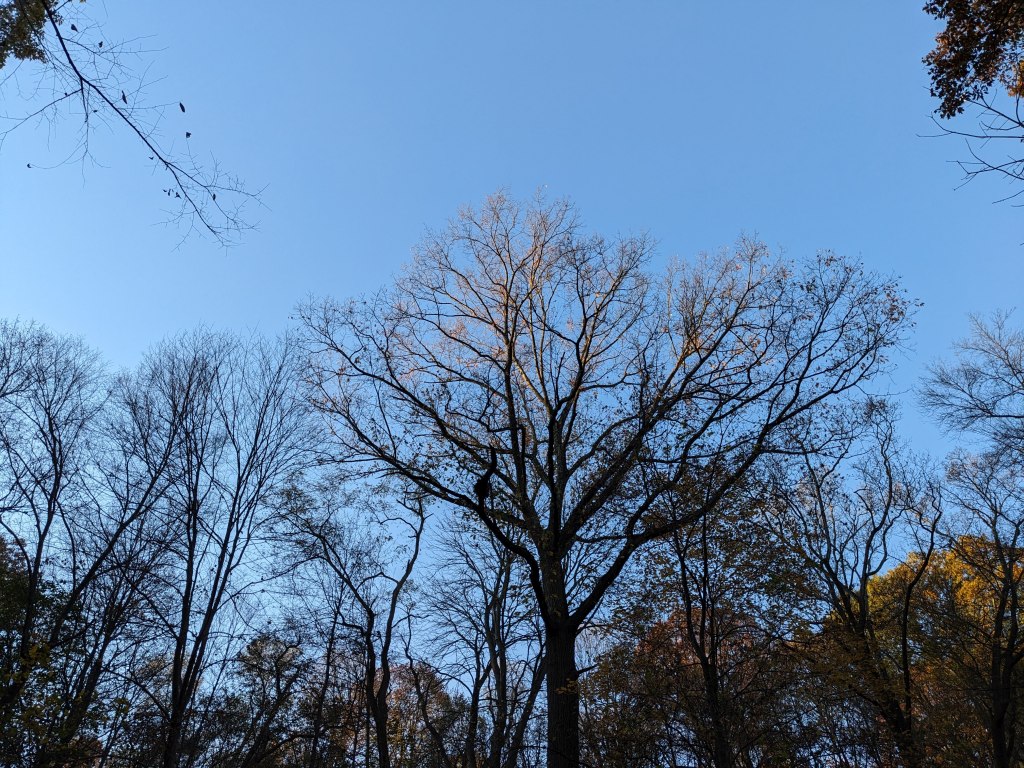

But now the trees are bare.

Bonus! Did you notice the clean hole in the center nut in my three-nut photo? It was probably made by a pecan weevil (Curculio caryae). The weevil drills a hole to lay its eggs inside developing hickory nuts, including pecans.

How does she drill into the nuts? Check out this video of acorn weevils drilling and mating.

Read more about pignuts at the Glen Arboretum.

(credits are in the captions)

13 November 2023

Warbler migration is over and waterfowl migration has not yet reached Pittsburgh so at times we seem to be in a birdless state. The Monongahela River at Duck Hollow was in that condition at yesterday’s Duck Hollow outing — a dozen mallards and 1(!) Canada goose — but we found a few good birds in the thickets.

When we arrived the sky was brilliantly blue with some russet trees on the hillsides. Our group of five was so small that we didn’t do go-around-the-circle introductions and I forgot to take a group photo.

One golden-crowned and three ruby-crowned kinglets bopped around us as we looked up this hill.

Best birds of the day were five purple finches (Haemorhous purpureus) — one male and four females — that were too far for a photograph, so here’s one from Wikimedia. We parsed out the females first: Very brown stripes on chest, wide white eyebrow, brown face, brown head, notched tail.

Then we saw the lone male (again this photo is from Wikimedia). House finches were nearby for comparison. Here’s how to tell the difference –> Purple and House.

Later a northern mockingbird came close for a photo, this one by Charity Kheshgi.

View our checklist online at https://ebird.org/checklist/S154301974 and below.

Duck Hollow, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

Nov 12, 2023 8:30 AM – 10:15 AM

5 participants, 25 species

Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) 1

Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) 12

Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) 3

Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus) 3

Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) 2

Red-shouldered Hawk (Buteo lineatus) 1

Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) 1

Belted Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon) 1

Red-bellied Woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus) 1

Downy Woodpecker (Dryobates pubescens) 1

Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus) 1

Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) 5

Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis) 3

Ruby-crowned Kinglet (Corthylio calendula) 3

Golden-crowned Kinglet (Regulus satrapa) 1

Carolina Wren (Thryothorus ludovicianus) 4

European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) 1

Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) 3

American Robin (Turdus migratorius) 8

House Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) 8

Purple Finch (Haemorhous purpureus) 5

American Goldfinch (Spinus tristis) 5

White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis) 8

Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) 3

Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) 6

(credits are in the captions)

11 November 2023

Songbird migration is quiet now and birds, when they’re found, are in mixed species flocks.

On 7 November, Charity Kheshgi and I encountered agitated golden-crowned kinglets, tufted titmice and dark-eyed juncos but it took us a while to find what they were upset about. This red morph screech-owl was hiding above our heads in a small oak.

An exception to the mixed species flocking rule is our “murder” of crows. My guess is that Pittsburgh’s winter crow flock is 90% American and 10% fish crows, but who can tell? They look alike.

In late afternoon crows stage in the trees in Shadyside and Squirrel Hill, then head west at sunset. 6,000 to 10,000 pass by my building on their way to the roost.

At sunset black birds in a darkened sky are impossible to photograph but it’s another story at sunrise. Click on the photo below for a closeup of crows in the brightening sky.

Leaves littered the ground this week and the air was filled with the sound of leaf blowers. 🙁

Most of the trees were bare in Schenley Park by Friday 10 November.

And finally, a reminder that the rut is still in progress and deer are crossing roads. This duo showed up at a Squirrel Hill polling place on Election Day at a place surrounded by roads. So watch out.

(credits are in the captions)

8 November 2023

Though their names differ by only one letter bitternuts and butternuts are not the same at all.

Bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis) is one of the most common hickories in southwestern Pennsylvania and easy to identify by its slender sulfur-yellow buds.

Bitternuts are closely related to pecans and also share the hickory genus with shagbark hickories, pignuts and mockernuts. Unlike the pecan the bitternut tree is rarely cultivated.

The fruit is a very bitter nut, 2–3 cm (0.75 – 1.25 in) long with a green four-valved cover which splits off at maturity in the fall, and a hard, bony shell.

— Wikipedia: Bitternut hickory

The “green four-valved cover” turns brown after the nut lies around for a while (see middle nut at top) and indeed the shell is hard and bony. I had to use a hammer to open this one and damaged the perfect nutmeat in the process. You’ll have to imagine it was shaped like a short squat pecan.

I can tell you from taste-testing that the nut is bitter and astringent. Squirrels avoid these nuts though Wikipedia says that rabbits eat them.

Butternuts (Juglans cinerea), on the other hand, are prized because the nuts taste good.

Butternuts are in the same genus as black walnuts and sometimes called “white walnuts.” The leaf arrangement is so similar that I didn’t realize that I was looking up at a butternut tree — to see warblers — until I saw the nuts on the ground.

Notice how similar the husks are: butternut on the left, black walnut on the right below. The butternut husk is oblong and fuzzy.

As the husk deteriorates (at left) the lumpy nutshell is revealed.

A cross section of the nut shows the rough exterior and nutmeat inside.

The butternut’s natural range runs from Maine and southern Ontario to southeastern Missouri and is smaller than the bitternut hickory’s. While the bitternut thrives, the butternut is declining and listed as threatened in some U.S. states and endangered in Canada. Its biggest threat is a fatal disease, butternut canker, caused by a fungus imported with the Japanese walnut. Ironically butternuts are partly threatened by too-easy hybridization with Japanese walnut trees.

Like black walnuts, butternuts are shade intolerant and thrive only when they’re at the top of the canopy or in an open space. Now that I know what a butternut looks like, I’ll pay more attention.

(credits are in the captions)

4 November 2023

Throughout October Pittsburgh’s city neighborhoods had not experienced a freeze, even though it was felt in the outlying areas. That changed on the first two days of November with a whisper of snow. We still had fall colors before the freeze. There are brown leaves and bare trees in our future.

At top, landscaping plants are often bred to maximize fall color as seen on a cultivated witch hazel on 28 October.

The oozing “sweat” beads on this polypore mushroom are just the right color for autumn.

Heavy mist on 29 October clung to ornamental grasses at Phipps Conservatory.

Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) was still blooming last week. Alas, it’s invasive.

The dawn redwoods (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) at Phipps change color before they lose their needles.

Fall color was muted on a misty morning in Schenley Park, 29 October.

(photos by Kate St. John)