9 February 2023

Here’s a first look back at my WINGS trip to Mindo and the Northwest Andes. I guarantee I’ll write more about Ecuador in the days ahead.

First a big thank you to WINGS Birding Tours, our superb group leader Jon Feenstra, skilled driver Edwin (who was also a great bird finder), and fellow participants Bob, Mary, Peter, Gail, Jeff, David and Kay. We all had a great time and became friends. It was hard to leave.

Even though I’d seen some of Ecuador’s birds in Costa Rica and Panama I came away with 206 Life Birds!

I was hard to pick only a few Best Birds.

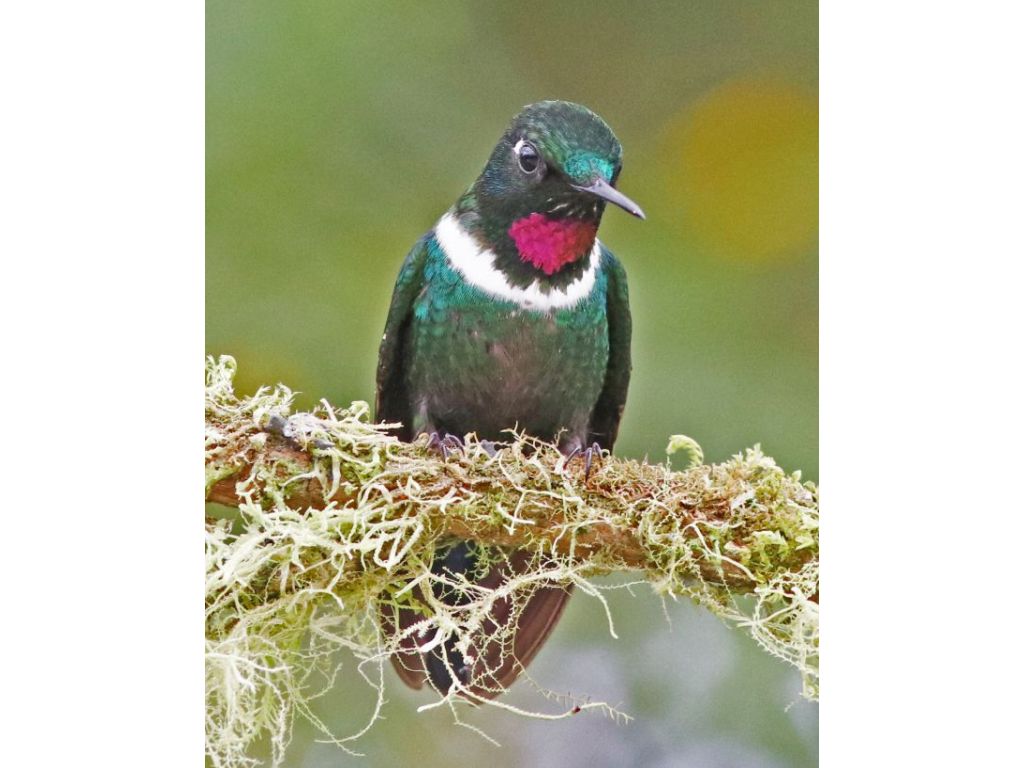

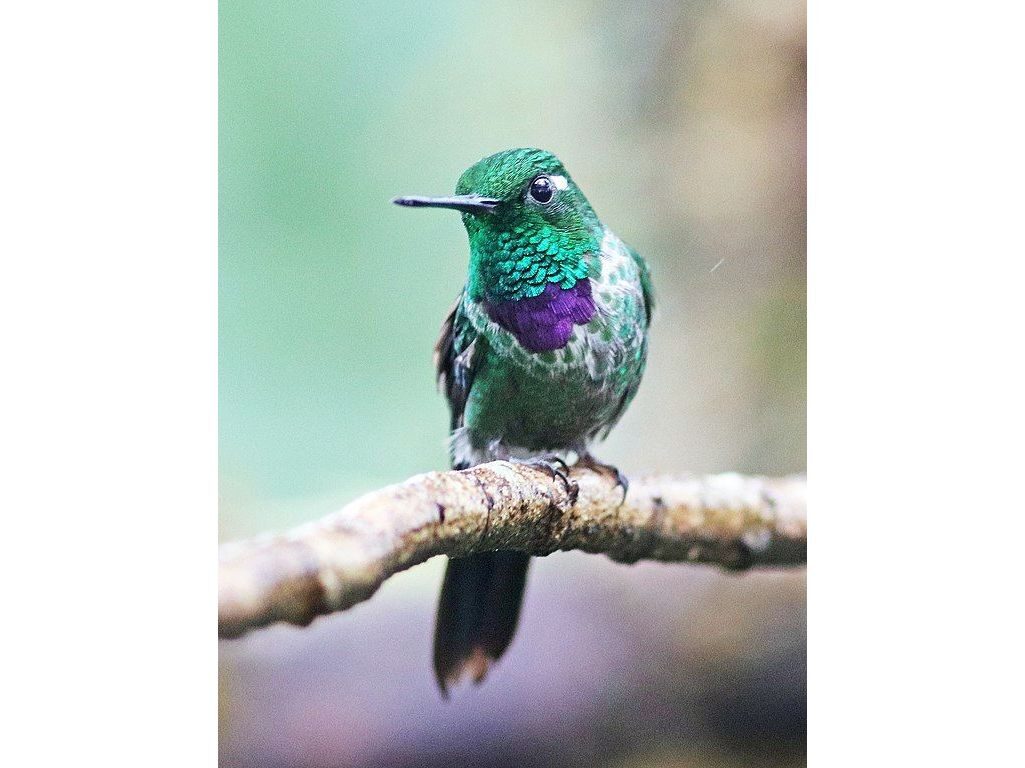

Best Hummingbird: I saw 31 species of hummingbirds on the trip so it was hard to choose a Best one, however … The crowned woodnymphs (Thalurania colombica) I’d seen in Panama had purple crowns but in the Mindo area they are quite impressive with emerald green hoods and purple chests, shown at top. You have to see this bird move its body to appreciate that it usually looks dull and dark, then catches the light to reveal its stunning green head and brilliant purple chest. The best views were at Alambi Reserve where this video was filmed in 2018.

Best Tanager: Of the 40 species of tanagers I saw in Ecuador, my Best one was a three-way tie: Black-capped (Tangara heinei) and beryl spangled tanagers (Tangara nigroviridis) are similar but different …

… and the stunning blue-necked tanager (Tangara cyanicollis) glowed in the forest with a neon blue head and neck.

Best Big Birds were the swallow-tailed kites (Elanoides forficatus) that live in Ecuador year round. Though not a Life Bird they were exhilarating to watch and there were lots of them. This image is a plate from the Crossley ID Guide.

Unexpected Lifer: Water birds are few and far between in the Andes but Jon knew where to find them. On the way back to Puembo Birding Garden we stopped by the side of the road near Quito Airport and scoped the drainage pond. Ta dah! The gull of the mountains: Andean gull (Chroicocephalus serranus).

If you’re interested in a trip to Ecuador’s Mindo and Northwest Andes I highly recommend WINGS Birding Tours and Jon Feenstra.

p.s. A surprising discovery: There are no crows in Ecuador but there are many free-ranging dogs. Dogs lounged in the middle of village streets and on the pavement of quiet streets in Quito. Without scavenger crows, free ranging dogs were the ones to break into garbage bags on garbage day. To prevent this people in the countryside placed their garbage bags on waist high platforms and in Quito on the median of busy streets but the dogs crossed in front of traffic to get at the garbage. Dogs partially filled the crow niche.

Perhaps dogs make it a dangerous place for cats. In 8 days we saw only two cats.

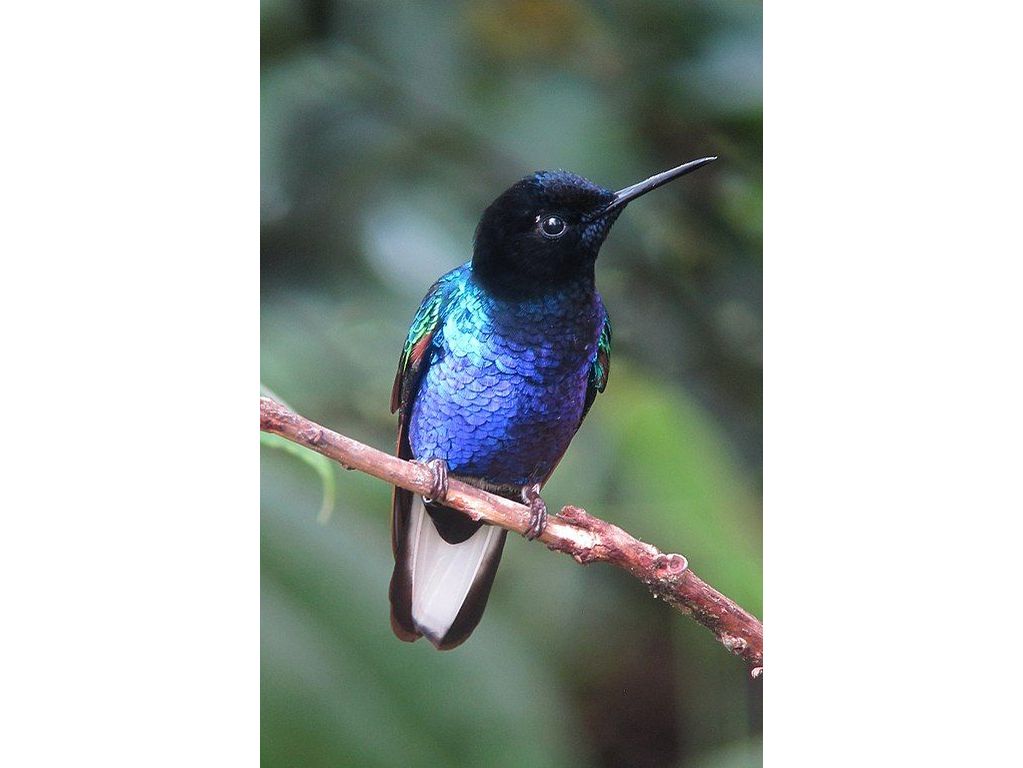

p.s. Looking back at the hummingbirds I’d say the velvet-purple coronet (Boissonneaua jardini) is a contender for first place.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons and Flickr via Creative Commons license; click on the captions to see the originals, video embedded from @andeanbirding on YouTube)