Two weeks ago I guaranteed you’d never see a roseate spoonbill in Pittsburgh and though “guarantee” is a dangerous word, I’ll use it again. I guarantee – this time with more certainty – that you’ll never see an American oystercatcher in the wild in Pittsburgh.

Why am I so confident of this prediction? Because American oystercatchers, unlike roseate spoonbills, have to live at the ocean. They specialize in eating saltwater bivalve molluscs (oysters, clams and mussels) using their razor-sharp beaks to cut the abductor chain that holds the two shells together. They are indeed oyster catchers.

They are also large, conspicuous and noisy. Their faces are clown-like with red-rimmed eyes and red-orange beaks. (The color is actually called Chrome Orange and is on their eyelids as well.) When flying they call “kleep, kleep, kleep, kleep, kleep, kleep” to each other. They are unmistakable.

American oystercatchers prefer sandy beaches, salt marshes and even saltwater dredge spoil piles. This keeps them beyond the bounds of southwestern Pennsylvania.

Brian Herman photographed this pair at Cape May, New Jersey.

(photo by Brian Herman)

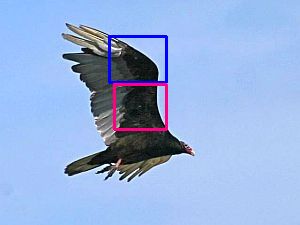

Today I’m back to wing anatomy and the huge topic of coverts.

Today I’m back to wing anatomy and the huge topic of coverts.