29 June 2017

Many birds molt once a year during summer’s “down time” between raising their young and fall migration. At this point their feathers have worn out.

Shown here are four primary feathers (remiges) molted by a black-legged kittiwake. It’s easy to see that these feathers are no longer in good shape for flight. Their edges are ragged.

Notice how the white barbs are in worse shape than the black ones. That’s because pigment adds strength to the feather. The darker the pigment, the stronger the feather. For this reason many sea birds have black tips on their white flight feathers and some birds have completely black primary and secondary feathers.

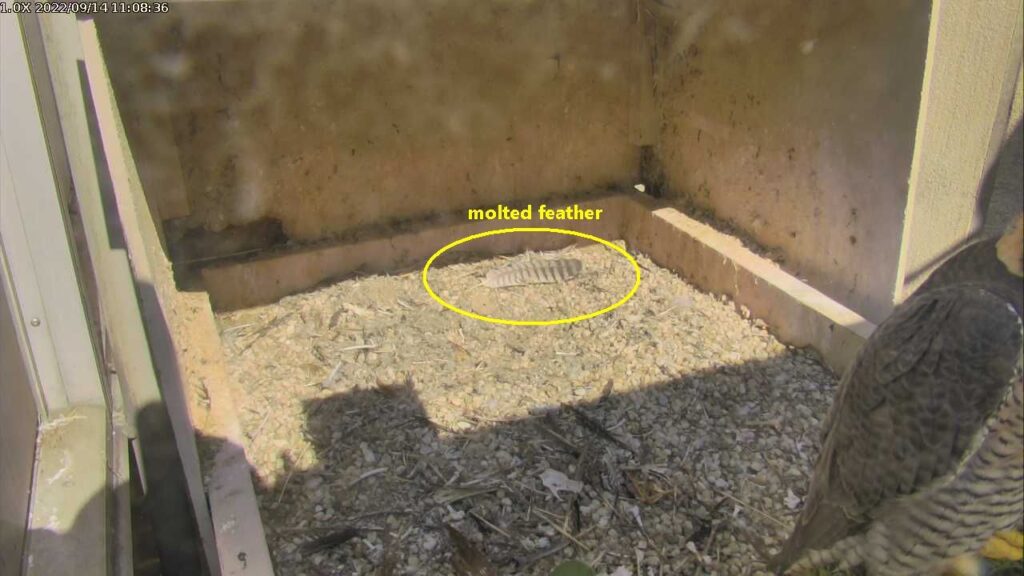

Adult peregrines molt once a year but it takes a long time. According to Birds of the World, resident peregrines in mid-latitude temperate zones (i.e. Pittsburgh) begin their molt in April and finish in September. The process takes 4.5 to 5 months to change out every feather but males and females don’t molt on the same schedule.

Male peregrines have to be in top hunting condition from May through June while the young need food at the nest and are learning to hunt. Males avoid replacing key flight feathers during that time.

However (news to me!) female peregrines begin to molt during incubation. This is a convenient time to do it because they’re temporarily sedentary and their mates supply their food. That’s why we sometimes see a peregrine feather in the nest box.

hi Kate — as usual, unrelated question: we have at least 2 mockingbirds in the back yard, very visible. When they see me or a cat they make a buzzy alarm call (?). But recently I hear (don’t see) someone calling peeeeeep (high-pitched, rising tone). It’s not the mockingbirds; could it be their hungry kids in nest? I thought catbird, but Cornell sample doesn’t sound like it.

Thanks — Kathy B

Kathy, yes you are hearing the begging call of a young mockingbird. So the nest was successful. 🙂

Interesting. Perhaps because they brood all their eggs at the same time for a considerable time that they were able to develop that habit. I wonder if any other birds that brood at the same time have similar molting habits.