On warm fall days look up and you might see swarms of flying ants. Flying high, they’re annoying at hawk watches. What are these ants and what are they doing? The answer is more interesting than you might think.

Flying ant swarms are the mating dance, the nuptial flight, of winged male ants and virgin queens. Each species has its own time of year for mating.

If you’ve never seen a swarm here’s what it looks like, filmed at a tall grass prairie in Nebraska (20 seconds).

The ants are so preoccupied with mating that they don’t pay attention to what’s nearby and are easy prey for migrating dragonflies, cedar waxwings, and even ring-billed gulls.

Don’t worry. The swarms are not termites. Termites make their nuptial flights in the spring and, if you look closely, they’re different from ants. Ants have pinched waists and “nodes” at their waistlines. Termites do not. Here’s a visual comparison — not to scale — of fire ants on the left and eastern subterranean termites on the right.

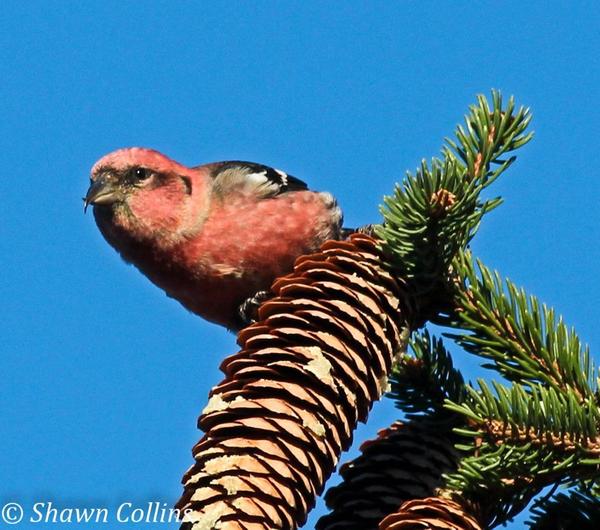

In autumn in Pennsylvania the swarms are sometimes citronella ants, Lasius interjectus (shown at top) or Lasius claviger, described here by Penn State Cooperative Extension. The name comes from their lemon smell when threatened or crushed.

Citronella ants spend their whole lives underground except when they emerge to mate. They’re actually “farmers” who tend their livestock — aphids — and harvest the aphids’ honeydew. This video describes a citronella ant colony.

After the nuptial flight the male ants die and the fertilized queens shed their wings. They don’t just shed them, they yank them off! Watch this citronella ant use two of her six legs to pull off each wing (7 seconds).

And then the queen walks off to find an underground place to nest.

There are so many ant species that it takes an expert to identify them. If you know which ones fly at the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch in September, please let me know.

(photo credits: citronella ant photo Lasius interjectus by Alex Wild via SmugMug, composite photo of fire ants and eastern subterranean termites from Wikimedia Commons. video credits: Ant swarm in Nebraska by Evan Barrientos on YouTube. Citronella ants by Chris Egnoto – The Naturalist’s Path on YouTube. Ant yanking off its wings by David Shane on YouTube)