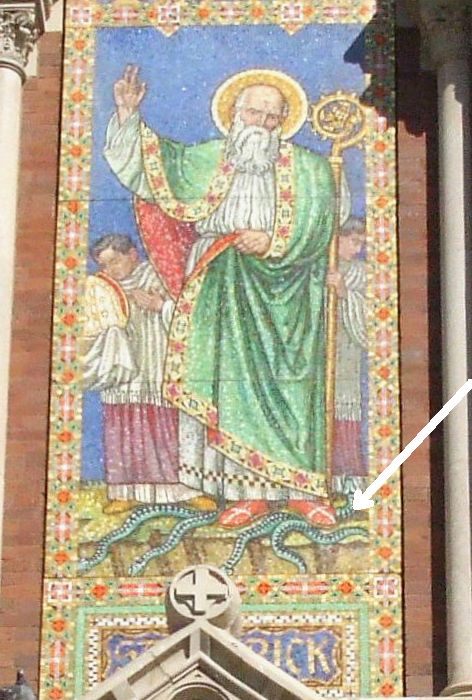

St. Patrick’s Day, 17 March 2021

Today we celebrate someone who banished snakes from an island.

Legend has it that St. Patrick, patron saint of Ireland, chased all the snakes into the sea after they attacked him during a 40-day fast.

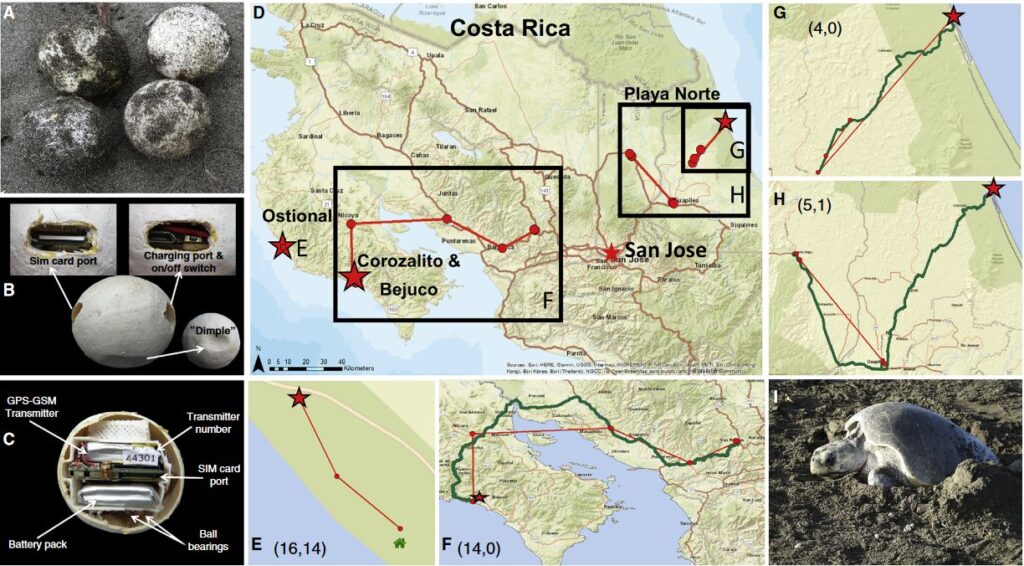

The island of Guam, a U.S. territory in the western Pacific, is plagued by brown tree snakes (Boiga irregularis) accidentally introduced after World War II. In 70 years the snake population exploded to 2 million, more than 100 snakes per hectare, or more 110 snakes per football field. It’s the highest concentration of snakes anywhere in the world.

Brown tree snakes have caused the extinction of most of Guam’s native wildlife, thousands of power outages, widespread loss of domestic birds and pets, and considerable emotional trauma to residents and visitors. Guam’s plant life has diminished, too, because the snakes have eaten the pollinators.

People working to eradicate Guam’s brown tree snakes have learned a lot about the animal. For instance, the snake dies when it eats acetaminophen so they’ve air-dropped acetaminophen-laced mice to tempt the snakes.

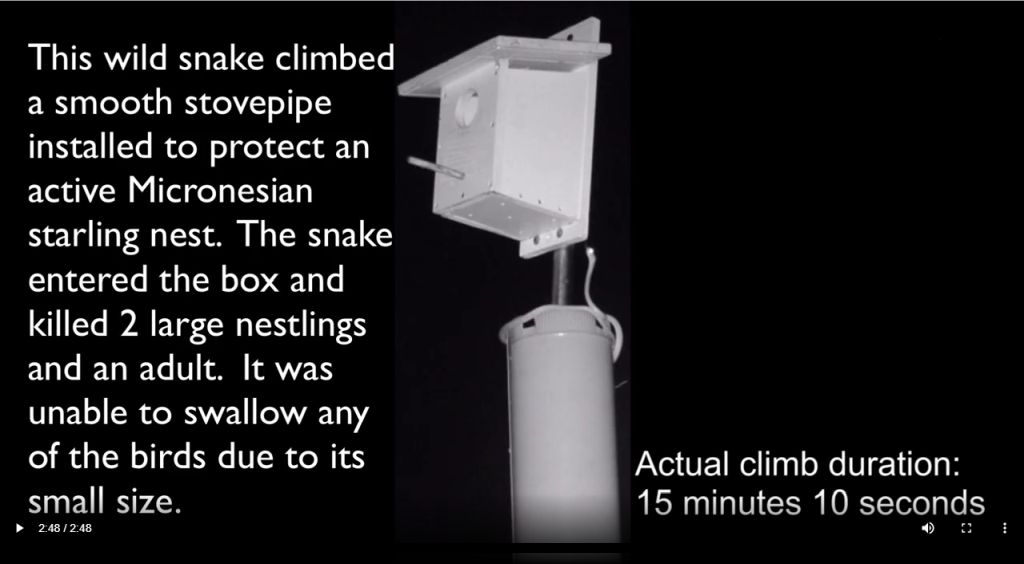

A study this year showed that fat slippery poles do not protect nest boxes so that method will have to change. The snakes make themselves into lassos to climb up! Click on the picture below or its caption to see a video of the snake in motion.

Everyone hopes that eradication efforts succeed and that Guam will celebrate No Snakes Day some time in the future. They could certainly use the help of St. Patrick and the luck of the Irish.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons an a screenshot from the lasso video; click on the captions to see the originals)