9 February 2022

With the spring equinox only five weeks away on 20 March, local songbirds have begun to sing to claim their territories.

Northern cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis) rejoined the soundscape in the last week or two. If you hear a loud “Cheer, Cheer, Cheer” look for the singer perched prominently nearby. Listen for two cardinals singing, one near one far, in this recording.

Song sparrows (Melospiza melodia) are some of the earliest to resume singing. They piped up in January.

Each male song sparrow has a unique variation on the basic song. The typical pattern begins with 3 introductory notes, then a warbling jumble that ends with a higher or lower note than the rest of the song. Here are two examples:

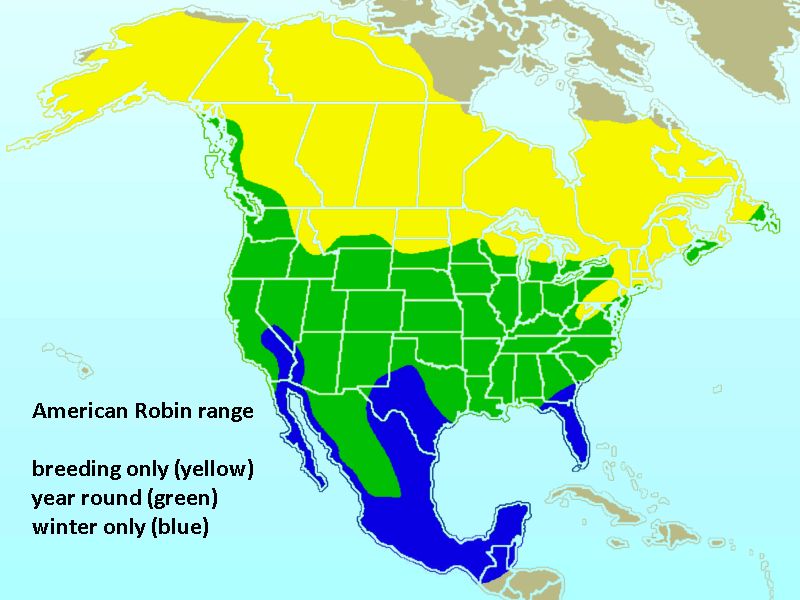

Though the flocks of American robins (Turdus migratorius) in Pittsburgh now are probably migrants that will leave in March, they can’t help but sing in fine weather.

Listen for their “Evening Song” at the end of the day.

When the sun shines in early February some other birds sing, too, including Carolina wrens and tufted titmice.

Get your ears in tune while there aren’t many singing so you’ll be ready when they all sing at once in April.

(photos by Peter Bell and from Wikimedia Commons; click on the caption to see the original)