27 September 2021

During fall migration warblers pass through Pittsburgh, followed by thrushes, then sparrows. We see them during the day after they’ve flown all night. Where were they yesterday? How far will they fly tonight? How fast are they traveling? What is their destination?

The answers are weather dependent, of course, but they also vary by species. Here are three recent songbird examples.

Wood thrush (Hylocichla mustelina)

Wood thrushes (Hylocichla mustelina) breed across the eastern U.S. and southeastern Canada, then spend the winter in Central America.

In 2009 a geolocator study of wood thrushes by Bridget Stutchbury found that:

- Wood thrushes fly more than 311 miles a day on migration. If they fly 8-10 hours per night their air speed is 30-38 miles per hour.

- They dawdle in the fall by stopping over in the southern U.S. or the Yucatan for one to four weeks before proceeding to their final destination.

- Wood thrushes return two to six times faster in spring because they barely stop at all.

- They shorten the trip by flying across the Gulf of Mexico overnight, a distance of 600 miles from the Yucatan to Louisiana.

Where was that wood thrush yesterday? Maybe north of Toronto, Ontario. When he leaves how far will he fly? Perhaps to Lexington, Kentucky.

Blackpoll warbler (Setophaga striata)

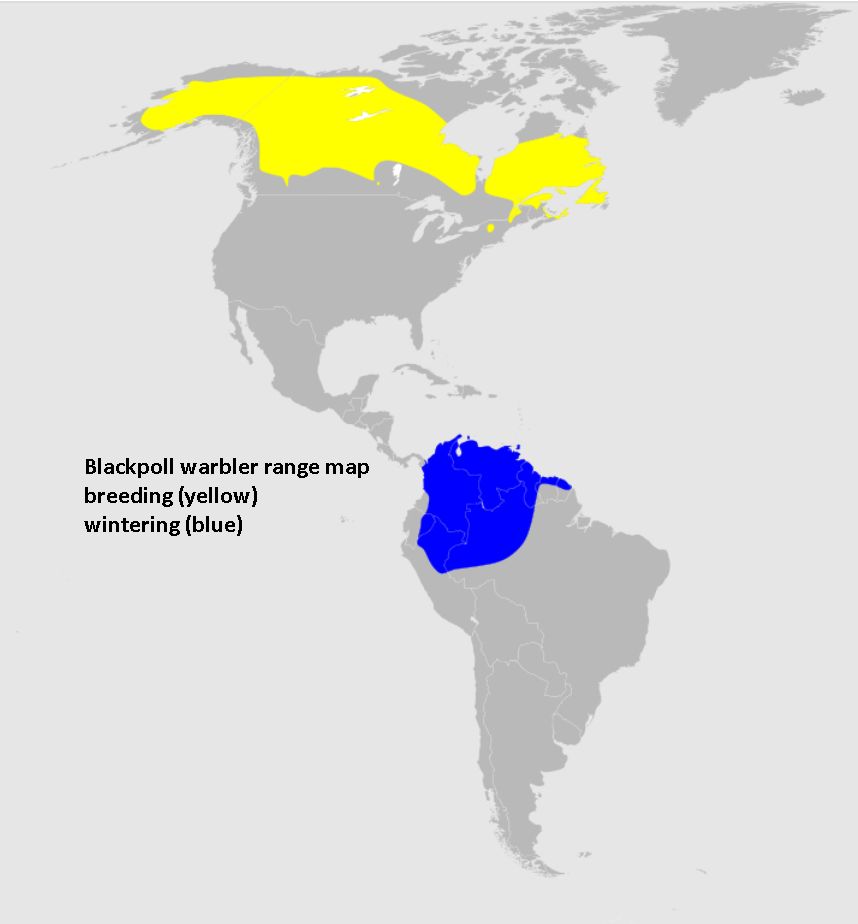

Blackpoll warblers (Setophaga striata) spend a lot of time fattening up before they leave North America for their wintering grounds in Brazil because they fly non-stop over the Atlantic Ocean to get there.

Their route averages 1,900 mi (3,000 km) over open water, requiring a potentially nonstop flight of around 72 to 88 hours. They travel at a speed of about 27 mph (43 km/h).

— Wikipedia Blackpoll Warbler account

Some blackpolls take off from Cape Cod. Some launch from coastal Virginia. Where was that blackpoll yesterday? If you’re asking this in Pittsburgh he might not have been very far north. Where will he be tomorrow? If you’re asking this on the U.S. coast the answer is “over the Atlantic Ocean.”

American robin (Turdus migratorius)

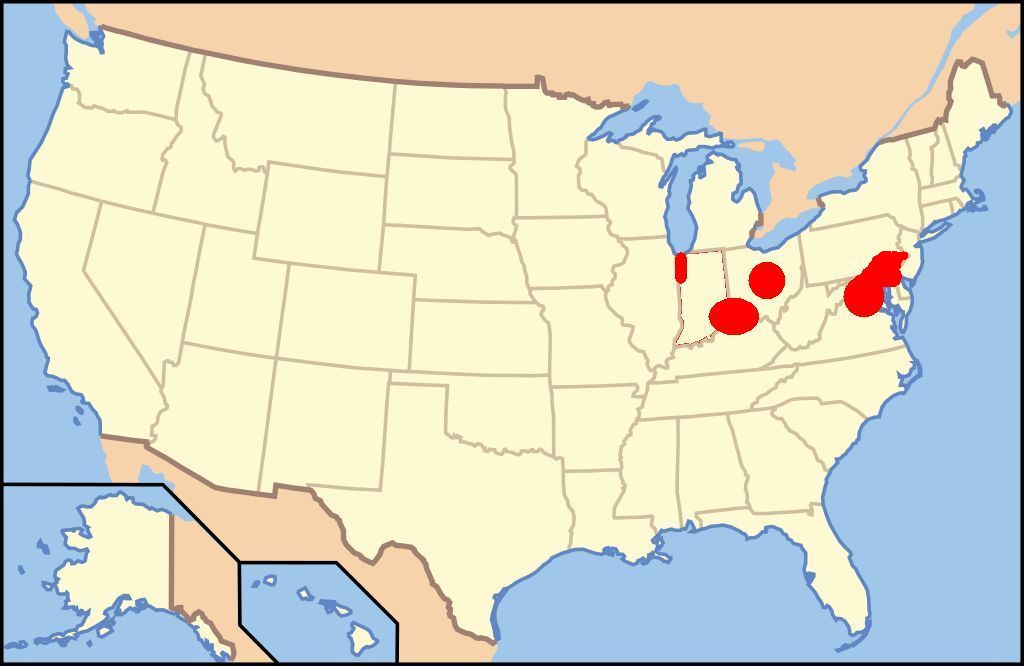

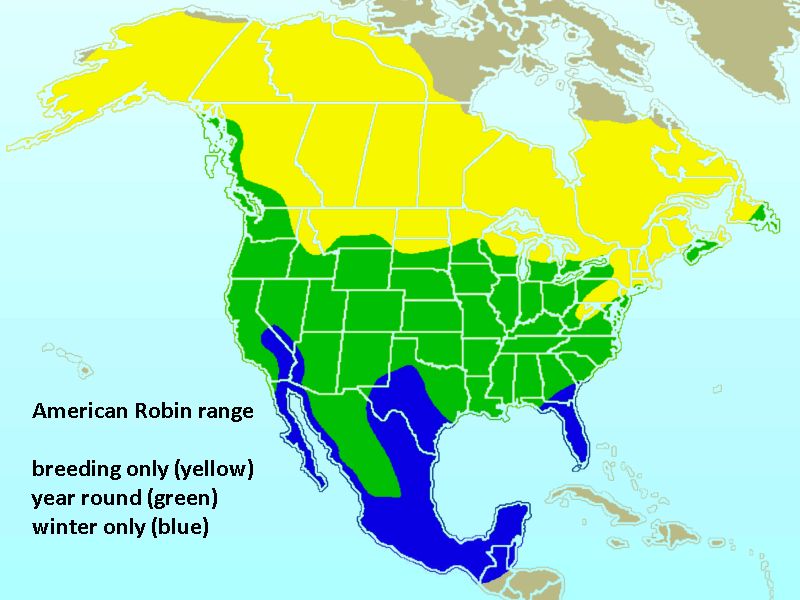

American robins (Turdus migratorius) take their time in the fall. Since they can live year round in much of the U.S. those that leave their breeding grounds (yellow on map) can afford to linger on their way south. Robins leave when the ground freezes or is covered by snow. Some travel as far as Florida, Mexico and Central America but most do not.

When on the move American robins have been clocked at 20-36 mph. They are faster when migrating than when they fly in our backyards.

So where was that robin yesterday? Probably here in Pittsburgh. Where will he be tomorrow? If he decides to fly all night he can reach Lexington, Kentucky with the wood thrush.

(photos and maps from Carl Berger on Flickr and Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals)