Here’s a tree that will soon disappear from western Pennsylvania, a victim of the emerald ash borers that arrived here in 2007.

White ash (Fraxinus americana) is easily identified by its twig with the chocolate-brown bud. The twig is stout, the leaf buds are opposite each other, the leaf scar is a horseshoe shape under each leaf bud, and all the buds are chocolate brown. (Click here for definitions of twig anatomy.)

It’s easy to find these buds in our area. There are many white ash seedlings now because the trees have put out a lot of seed while they’re under attack.

Opposite leaf buds are a good marker for the ash because most trees have alternate leaves. The main species with opposites are maples, ashes, buckeyes and dogwoods. I learned to remember opposite leaves with the acronym MAB DOG (Maple, Ash, Buckeye and Dogwood).

White ash bark is distinctive too. Its deeply ridged and the ridges join to form long diamond shapes as shown below.

.

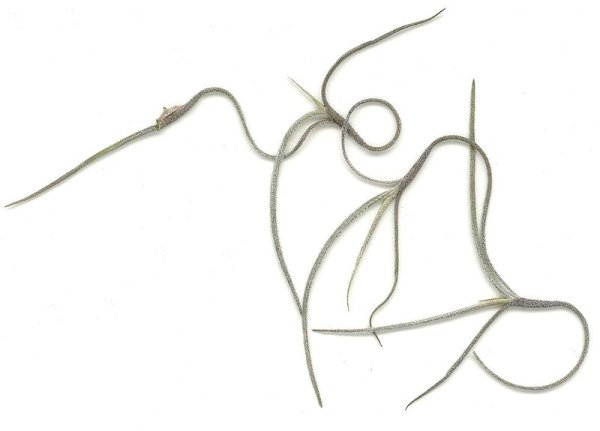

Unfortunately, larvae of the emerald ash borer kill the tree by tunneling under the bark and damaging the phloem and xylum. Often this causes the ridges to slowly separate from the bark. Woodpeckers hear the larvae (amazing!) and chip away at the ridges to get at the bugs. The result is that a dying tree has pale patches where the ridges fell off. Infected trees try to survive by sending out sprouts near the ground. You can see both effects on the trunk below.

.

If you examine the chipped bark closely you may find the D-shaped exit hole of the emerald ash borer. (Thanks to Dianne Machesney for this photo.).

.

Learn the white ash now. Sadly, it won’t be with us much longer.

(photos by Kate St. John, except for the one noted by Dianne Machesney)