18 January 2022

On the recurring subject of sea eagles …

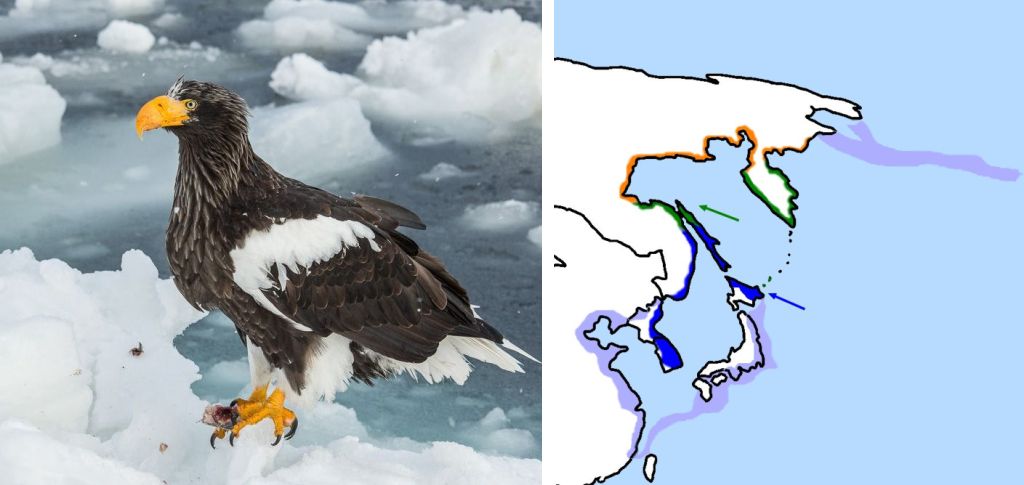

The Steller’s sea eagle in Maine was still near Boothbay Harbor on Tuesday 18 January 2022, as reported by @WanderingSTSE. The bird is 7,000 miles away from his native range and the only member of his species on the continent. What would his life be like if he was at home?

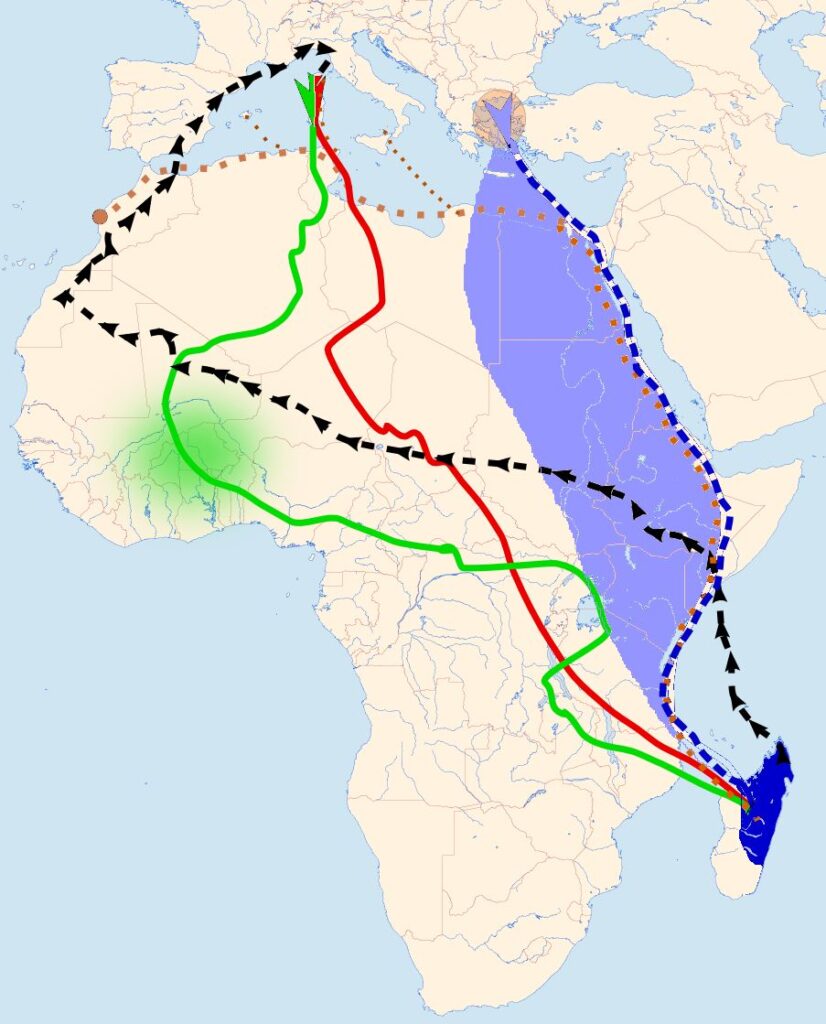

Steller’s sea eagles (Haliaeetus pelagicus) breed in Far Eastern Russia and migrate south for the winter but they don’t leave cold weather behind. One of their favorite winter locations is Hokkaido, Japan where floating ice provides a platform from which to fish. (Blue arrow points to Hokkaido.)

They are joined there by a smaller sea eagle, the white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) of Europe, Asia and western Greenland. White-tailed eagles are very similar to their closest relative, the bald eagle. All three are sea eagles in the genus Haliaeetus.

At Hokkaido the sea eagles have a daily banquet on the ice.

p.s. 18 Jan 2022 UPDATE on the Steller’s sea eagle in Maine:

Jan 18th Update: Early morning sightings around the Maine State Aquarium (West Boothbay Harbor, Maine)!#StellersSeaEagle

— Steller’s Sea-Eagle (seen 1/18 in Maine) (@WanderingSTSE) January 18, 2022

(photos from Wikimedia Commons, video by John Russell embedded from YouTube; click on the captions to see the originals)